Overview

As communities across the country struggle to end homelessness, two new free screening tools from the Economic Roundtable can help thousands of the most vulnerable people get access to the public services they need as soon as they become homeless, or even before they are homeless.

The first tool identifies the eight percent of low-wage workers who become persistently homeless after losing their jobs. The second tool identifies the eight percent of youth receiving public assistance who become persistently homeless in the first three years of adulthood. These tools have been placed in the public domain for free use in cities throughout the United States.

The first tool identifies the eight percent of low-wage workers who become persistently homeless after losing their jobs. The second tool identifies the eight percent of youth receiving public assistance who become persistently homeless in the first three years of adulthood. These tools have been placed in the public domain for free use in cities throughout the United States.

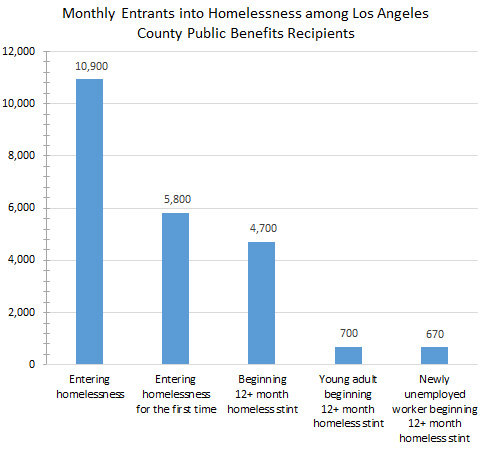

In major U.S. metropolitan areas, the number of long-term homeless needing housing far exceeds the available housing supply, making it difficult to move persistently homeless individuals off of the streets. One of the most promising approaches to reducing these numbers lies in early identification and quick, effective intervention to help those most likely to become persistently homeless.

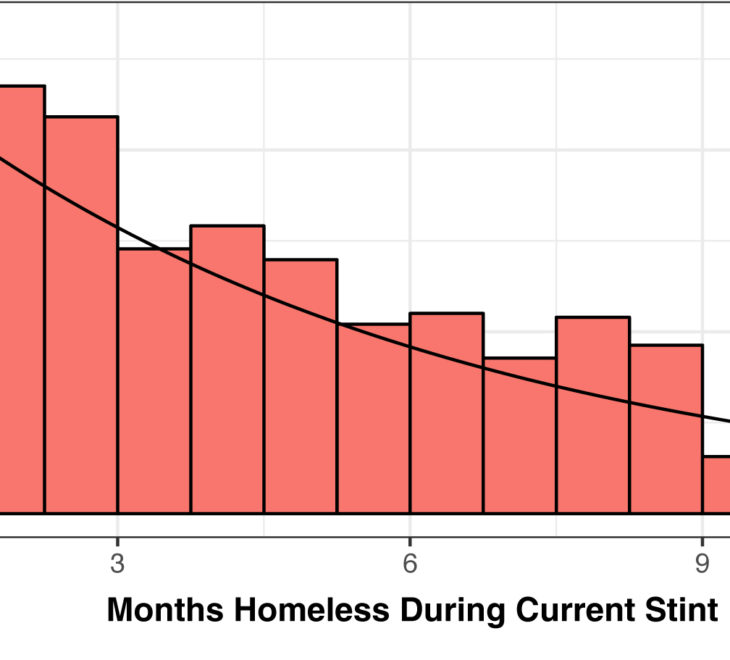

A majority of people entering homelessness over the course of a year make rapid exits, often with little help, but roughly two-fifths become persistently homeless, which is defined as 12 consecutive months of homelessness, or two or more episodes of homelessness within three years. These screening tools are valuable for identifying individuals who will remain stuck in homelessness.

It is reasonable to use the tools in metropolitan areas throughout the United States, based on the large and broadly representative study population used to develop the tools, and the scarcity of comparable information for other regions. The study population includes nearly everyone who was homeless in Los Angeles County during a fifteen year time window, a total of over one million people, in the most populous county in the United States. This definition of homelessness includes individuals who are couch surfing, which is broader than HUD’s definition of sleeping in a place not meant for human habitation.

The tools can be reconfigured to use locally available data and still retain a high level of accuracy, provided that key attributes of individuals are addressed. This includes demographic characteristics, homeless and employment histories, and use of services provided by the health, behavioral health, social service, and justice systems.

Using Predictive Analytic Models to Guide Homeless Interventions

Because it is hard to differentiate newly homeless individuals who will make rapid exits from those who will remain stuck in homelessness, the prevailing service delivery model calls for “progressive engagement.” Progressively more help is given as individuals remain homeless longer. If individuals become chronically homeless, they are offered permanent supportive housing, if units are available.

Progressive engagement is pragmatic, but it gives rise to two problems:

Progressive engagement is pragmatic, but it gives rise to two problems:

- The longer people are homeless, the worse their problems become, making it more difficult and expensive to stably house them.

- The flow of people into long-term homelessness is not reduced, so there is growing demand for the most expensive homeless intervention, permanent supportive housing, and meeting this demand is challenging.

Predictive analytic models can distinguish accurately between different types of homelessness and predict future outcomes. This can improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of homeless interventions. For example:

- Predictive models can provide a fair, objective system for prioritizing who gets to be housed based on likely duration of homelessness or public costs in future years.

- Predictive models can identify newly homeless individuals who are likely to become persistently homeless so they can be targeted for early interventions that will help them escape homelessness with less distress and public cost.

In addition to housing chronically homeless individuals, the most promising strategy for combating homelessness is to have tools for differentiating level of need among newly homeless individuals and to intervene early with intensive help for individuals who are likely to become persistently homeless. The payoffs are:

- Interventions can be provided that are specifically tailored to meeting the needs of discrete high-risk subpopulations.

- Small reductions of the flow of people into chronic homelessness will have a large impact on reducing the number of people who are chronically homeless.

- Individuals will have far less social, economic, legal, and medical damage in their lives, making it more feasible and less costly to help them become stably housed.

Workers Who Lose Their Jobs and Become Persistently Homeless

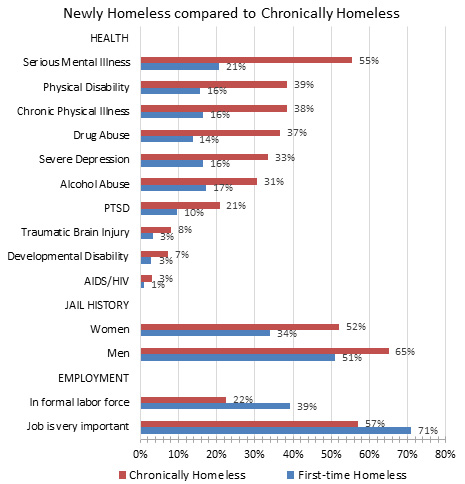

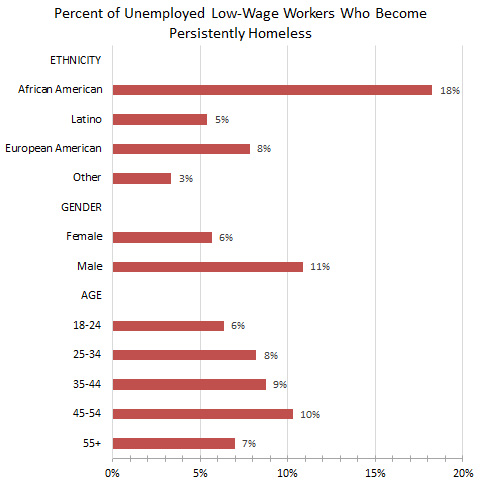

All low-wage workers face some level of risk that they will become persistently homeless if they lose their jobs, but this risk is disproportionately high for workers who are African American, male and single. It is important that screening to identify unemployed workers who are likely to become persistently homeless be carried out in ways that effectively reach these groups with especially high-risks.

Over the course of homelessness, the widening monthly cost gap for local public services and higher cumulative costs for workers who become persistently homeless provides financial justification for a comprehensive package of re-employment services to avoid higher long-term costs. The predictive analytic tool described in this report can target high-risk workers for a package of re-employment services as soon as they lose their jobs, before they become homeless.

Over the course of homelessness, the widening monthly cost gap for local public services and higher cumulative costs for workers who become persistently homeless provides financial justification for a comprehensive package of re-employment services to avoid higher long-term costs. The predictive analytic tool described in this report can target high-risk workers for a package of re-employment services as soon as they lose their jobs, before they become homeless.

Some high-risk workers have barriers to employment resulting from substance abuse and involvement in the criminal justice system. This indicates that some need behavioral health services to overcome substance abuse problems as well as legal services to expunge or lessen their criminal justice records.

One quarter of high-risk workers are part of a family unit and one third are homeless before they lose their jobs. This indicates that some workers need affordable child care and many workers need affordable transitional housing.

Almost one third of workers who become persistently homeless have held down jobs despite having limiting physical or mental conditions. These disabilities become much more frequent during post-unemployment homelessness. These workers are likely to have better employment and job retention prospects if they receive health care support in treating and managing their conditions. These conditions most frequently involve back, joint and arthritic problems. These workers will benefit from finding work in occupations that are less physically demanding than their previous jobs.

Workers who become persistently homeless often have histories of job turnover, under-employment and low earnings. This indicates that many high-risk workers need education and training that will enable them to compete for better jobs. They may also need temporary housing and wage subsidies to encourage employers to give them an opportunity to demonstrate their capabilities.

Young Adults Who Become Persistently Homeless

The young adult screening tool is designed to identify the eight percent of young adults receiving public benefits who will become persistently homeless within three years.

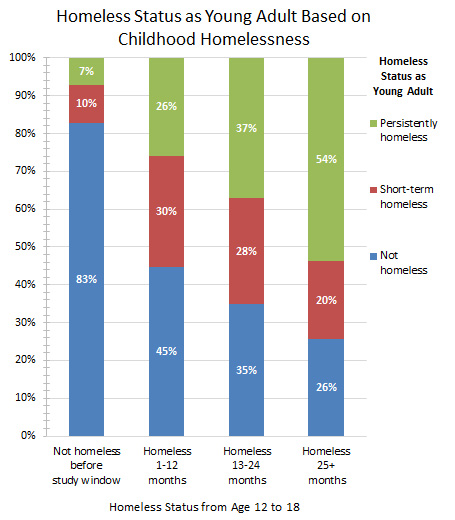

Youth who become persistently homeless are far more likely to be solitary and not connected to a family unit. Youth who experienced homelessness in their six years preceding adulthood were more than three times as likely to be homeless as young adults than those who had not previously been homeless. The risk of persistent homelessness is especially high for:

Youth who become persistently homeless are far more likely to be solitary and not connected to a family unit. Youth who experienced homelessness in their six years preceding adulthood were more than three times as likely to be homeless as young adults than those who had not previously been homeless. The risk of persistent homelessness is especially high for:

- African American youth

- Youth who have been in the foster care system

- Youth who were homeless as children

- Youth who are homeless when they enter adulthood

- Youth who have been incarcerated

It is important that screening to identify young adults who are likely to become persistently homeless be carried out in ways that effectively reach these groups with especially high-risks.

Substance abuse problems increase the likelihood of justice system encounters and are much more prevalent among youth who are persistently homeless. Many high-risk young adults need behavioral health services to overcome substance abuse problems, and some need legal services to expunge or lessen their criminal justice records.

Only five percent of the young adult population spent time in the foster care system, but 13 percent of those who were persistently homeless had been in foster care.

The enactment of California Assembly Bill 12 in 2012 extended foster care services until youth are 21 years old. It has improved but not eliminated the problem of youth homelessness. Youth who were eligible for extended foster care services under AB 12 had better outcomes – 16 percent of these youth experienced persistent homelessness compared to 24 percent of older foster youth who emancipated into adulthood when they were 18 years old, before the bill took effect.

Disabilities emerged rapidly among young adults who were homeless – a quarter of persistently homeless youth had persistent disabilities at the end of the three-year study window. The largest share of these disabilities were for mental conditions. Effective early intervention for young adults who are on a path toward persistent homelessness can reduce the rapid emergence of long-term physical and mental disabilities that result from continued homelessness.

Persistently homeless youth have higher employment rates but lower earnings than their peers who are not stuck in homelessness. This demonstrates a strong drive to earn enough money to pay for housing but little success in obtaining sustaining employment. Many high-risk young adults need human capital investments in the form of education and training that will enable them to compete for better jobs. They may also need wage subsidies to encourage employers to give them an opportunity to demonstrate their capabilities.

Young adults who become persistently homeless often have histories of social disconnection, high level of effort to find employment but low earnings, and behavioral health needs. This indicates that many high-risk young adults need education and training that will enable them to compete for better jobs, and behavioral health services. They may also need affordable housing and wage subsidies to encourage employers to give them an opportunity to demonstrate their capabilities.

Public Costs

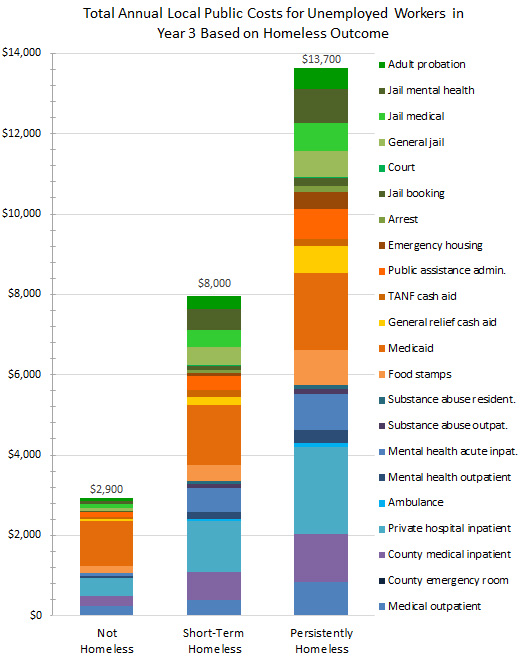

Individuals who become persistently homeless use more public services and have far higher public costs than their peers who do not become homeless. These costs are ongoing and increase as individuals become older.

Health care costs were five times higher for persistently homeless workers and four times higher for persistently homeless youth than for their counterparts who did not become homeless.

Health care costs were five times higher for persistently homeless workers and four times higher for persistently homeless youth than for their counterparts who did not become homeless.

Justice system costs were nine times higher for persistently homeless workers and seven times higher for persistently homeless youth than for their counterparts who did not become homeless.

Using predictive screening tools to identify high-risk individuals and intervene early before they become persistently homeless can help them avoid hardship and help the public avoid continuing high costs from ongoing, intensive and increasing use of local services.

Conclusions

Both predictive models are very accurate and particularly strong when using high probability cutoff levels for targeting high-risk individuals. A key strength of the models is that the accuracy of predictions was validated using three years of post-prediction data. Another key strength is that the models are transparent and identify distinctive attributes of high-cost individuals. The results confirm that local public costs for targeted individuals are likely to be high and to increase over time.

The tools are particularly useful for prioritizing unemployed workers and young adults for services because each individual who is screened is given a probability of becoming persistently homeless. Prioritizing individuals for access to early, comprehensive interventions is important because the resources that are most effective for preventing homelessness, including subsidized housing and employment, are scarce in relation to the demand for those resources.

The purpose of the models is to target individuals for additional help. Unlike models used to predict credit rating or justice system outcomes that have punitive consequences, the consequences for individuals targeted by these models are beneficial.

The optimal probability cutoff level for individuals who will be targeted for services is not simply an empirical decision but is influenced by resource availability and longer term cost avoidance. Greater program capacity for helping unemployed workers obtain new jobs and for helping young adults make a successful transition into adulthood can increase the percent targeted for help. Longer term public cost avoidance also should be considered in deciding on funding levels for delivery of these targeted services.

Both models are system-based tools. Depending on the population targeted, they require information about healthcare, justice system involvement, foster care, employment, homeless history, and demographics that is most readily available from the records of public agencies.

Because of the level of effort required to obtain and integrate the necessary data, the most efficient use of the tools is regular, ongoing system-wide screening of linked records. Screening clients individually is a fallback option. By using either system-wide or person-by-person screening to predict how likely each person is to become persistently homeless, it is possible to prioritize individuals for access to the scarce supply of housing and services.

Because the tools do not correctly identify all high-risk individuals, the screening process should include an option to override the probability score based on the judgment of service providers. Allowing overrides permits service providers to adapt to changing populations and conditions and to be responsive to unique circumstances.

The strong validation results for these models show that it is possible to develop many other predictive models that will target other distinct homeless populations for specific types of interventions. Each model is likely to target only a narrow segment of the overall homeless population because discrete population groups with distinctive attributes are needed to produce accurate predictive results. An updated typology of homelessness that breaks out distinct homeless trajectories will be valuable for mapping the full range of groups that should be targeted for interventions that will minimize the harm, cost and duration of homelessness.

Future Research

The Economic Roundtable has created a de-identified dataset of the records used for this research and provided it to Los Angeles County with the recommendation that it be made available to other researchers. The Roundtable is also seeking to use this dataset to develop new typologies of homelessness and additional tools for targeted interventions that will strengthen efforts to combat homelessness. The dataset is a powerful research tool for combatting homelessness in Los Angeles County and across the country.

This dataset complies with National Institute of Technical Standards guidelines for record de-identification. The National Institute of Technical Standards states that the risk of harm to human subjects from record re-identification should be weighed against the risk of harm to the public from withholding the information. “There may be a tendency for government agencies to either overprotect or under-protect their data. . . . For example, absent the data release, external organizations will suffer the cost of re-collecting the data (if it is possible to do so), or the risk of incorrect decisions that might result from having insufficient information.”

This link provides a chronology of discussions with Los Angeles County about this dataset. The use of this data is reported on in this article by the Los Angeles Times.

Press Coverage

Los Angeles: Why tens of thousands of people sleep rough

By Daniel Flaming and Gary Blasi, BBC (September 19, 2019)

Two-thirds of L.A.’s homeless are trying to find work. Let’s help them

By Daniel Flaming, Los Angeles Times (June 6, 2019)

Garcetti frustrated by decades-old homeless crisis

By Bill Boyarsky, LA Observed (June 16, 2019)

Will Los Angeles’ Homelessness Spike Lead to a Course Correction?

By Jessica Goodheart, Capital & Main (June 19, 2019)

L.A. spent $619 million on homelessness last year. Has it made a difference?

By Gale Holland, Los Angeles Times (May 11, 2019)

Homelessness Is Getting Worse In Southern California. Here’s Why

By Matt Tinoco, LAist News (May 10, 2019)

Will Algorithmic Tools Help or Harm the Homeless?

By Jack Denton, Pacific Standard (April 16, 2019)

A new study says it can predict homelessness. But L.A. County doesn’t want to use it

By Doug Smith, Los Angeles Times (March 21, 2019)

LA researchers offer tools to help those likeliest to stay homeless

By Elizabeth Chou, Los Angeles Daily News (March 20, 2019)

Is LA Waiting Too Long To Help The Newly Homeless? A New Report Says Yes

Matt Tinoco, LAist (March 21, 2019)

Stopping Homelessness before It Starts

By Michelle Chen, Dissent (April 1, 2019)

Can a New Screening Tool Help Solve the Crisis of Black Homelessness?

By Jessica Goodheart, Capital & Main (March 26, 2019)

There’s a tool to predict homelessness—and L.A. County is refusing to use it

Brian Addison, Long Beach Post (March 21, 2019)

What are the most common reasons people are homeless in Seattle?

By Scott Greenstone, Seattle Times (March 18, 2019)

Predicting homelessness

Sophia Bollag, The Sacramento Bee (March 20, 2019)

Predicting who’s likely to become homeless

Anna Scott, KCRW Morning Edition (March 21, 2019)

L.A. County Rejects Screening Tool to Prevent Homelessness, Accuses Nonprofit of Misusing Records

KTLA 5 (March 21, 2019)

Predicting Homelessness

By Matt Tinoco, KPCC, (March 22, 2019)

Homelessness Crisis in Los Angeles County

Richard Foster, BBC Radio 5 Live (March 22, 2019)

Dr. Drew Midday Live

Dr. Drew Pinsky, 790 KABC (March 26, 2019, 1:00 pm)