In his 1963 letter from the Birmingham jail Martin Luther King, Jr. described the despair of people “smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society.” It is important to understand the extent to which this image of entrapment still describes the wage-earning lives of the working poor as they try to support their families.

In his 1963 letter from the Birmingham jail Martin Luther King, Jr. described the despair of people “smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society.” It is important to understand the extent to which this image of entrapment still describes the wage-earning lives of the working poor as they try to support their families.

Welfare reform has increased labor force participation among welfare parents. But is work leading to self-sufficiency or another cycle of defeat for these workers? The answer is that most welfare workers remain trapped in the cage of poverty.

The basic premise of the work-first model that continuing participation in the labor force will lead to economic self-sufficiency has proven to be mistaken. Most welfare workers have been unable to move beyond jobs that are either part-time or short-term, or both. Less than one-fifth of these workers are able to gain entry into industries paying sustaining wages and work for at least three quarters a year over a multi-year period, which are the prerequisites for rising above the poverty threshold.

Full-time pay for workers in the lowest-paid 5 percent of jobs in the county economy, which includes 71 percent of all welfare workers who were reported to have found jobs and who have been back in the labor market for three years or more, is only one-fifteenth as much as for their highest-paid counterparts at the top of the county’s job ladder. These workers have no opportunity for asset development or for investing in their own communities. Their uphill struggle in trying to meet daily survival needs virtually debars them from building equity in the regional economy.

Assets such as education, vocational skills, livable neighborhoods, and financial capital empower individuals and communities to be self-sustaining and capable of adapting to economic change. These assets, however, are not equally accessible to everyone. For some they are virtually inaccessible. Resources and opportunities that increase productivity, earnings and asset accumulation include:

- Good public education.

- Access to higher education.

- Safe and decent housing.

- Reliable and timely transportation.

- Employer-provided training.

- Knowledge-based work experience.

- Employment in industries characterized by high levels of innovation.

- Employment in industries with sustained capital investment and upgrading.

- Interconnection through communication, transportation, and financial links.

- Access to capital through savings, credit or other means.

Many low-wage workers do not have access to even one of these resources that enable individuals to achieve sustained economic well-being. A fundamental requirement for enabling low-wage workers to rise out of poverty is to give them access to resources that will enable them to invest in themselves.

In the short-term, most welfare parents who have complied with welfare-to-work requirements have seen their incomes rise. Their earnings combined with partial welfare benefits have provided more income than they would have received through welfare alone. This outcome is beneficial but also temporary and precarious. There is no strategy or body of resources for providing income to welfare parents in the event of:

- A recession that brings rising levels of unemployment back to the region, or

- Administrative requirements to impose the five-year, life-time limit on public assistance that is part of federal law.

There is every reason to believe that many families will suffer acute deprivation and hardship when either of these events occurs. If both occur at the same time, the impacts may be disastrous.

In the latter half of the 1980s and early 1990s, conservatives, moderates, and liberals coalesced around the goal of ensuring that families in which a parent worked full-time, year-round would not be poor.[1] The growing number of working poor in Los Angeles County is at variance with this principle of economic justice.

An abundance of low-skilled workers attracts low-wage industries that can use them. To the extent that these industries grow and are the primary employers available, welfare workers will remain trapped in an insecure, low-wage labor market. The underlying problem of poverty is “more and more a problem of gainfully employed persons.”[2]

The long-term growth of poverty in Los Angeles County shows that exits from poverty are occurring less rapidly than entries into poverty. Despite overall growth in earnings in the county labor market over the past decade, 22 percent of county residents were in poverty in 1998. This is a very serious problem. A regional growth path in which low-paying industries become increasingly predominant and workers with marginal earnings are increasingly numerous will lead to increasing polarization of income between the affluent and the poor, declining per capita public revenues, and growing social problems that diminish the quality of life for everyone. The civil unrest of 1992 can be understood as a manifestation of rage over economic deprivation and blighted hopes.[3] Residents of the county share an essential interest in building a labor market that does not leave families in poverty. The entire regional economy benefits when workers break out of low-wage jobs.

The purpose of this report is to use the work histories of welfare-to-work participants during the decade of the 1990’s to map their job connections and understand the growth path being created in the county’s economy by this expanding sector of the labor force. These outcomes are important because Los Angeles County has more people below the poverty level than any other county in the nation, and more than all but four states.

Key Findings

We analyzed the employment records of nearly 100,000 welfare-to-work participants. This included everyone who was reported to have found a job from 1990 through 1997, and represents about half of the county’s welfare-to-work participants during this period. The half that was not studied faces even bleaker prospects than the workers we tracked. Central findings from this study of labor market connections include:

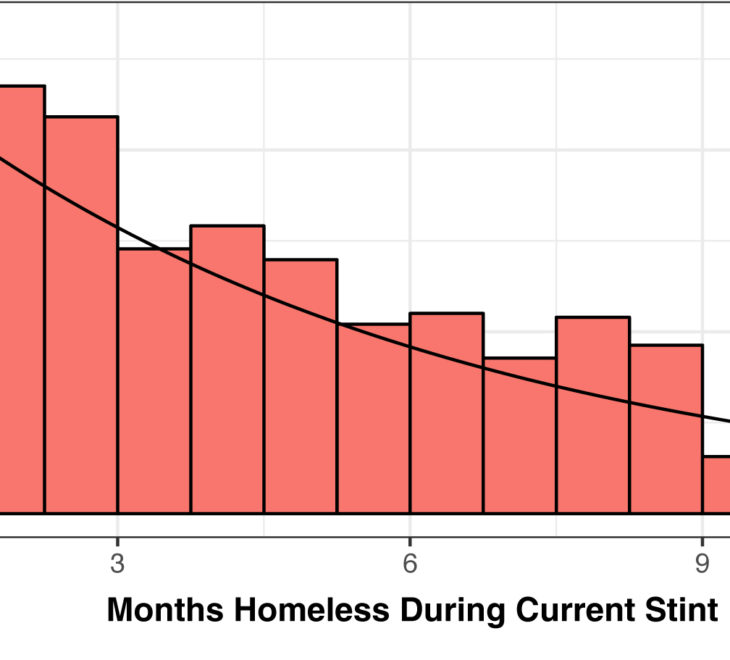

- Workers typically are employed two to three quarters a year in part-time, low-wage jobs. One-fifth of workers have two or more employers in the same quarter. Workers typically hold on to a job for two and one-half quarters before having to find a new employer. Wages combined with the Earned Income Tax Credit average about two-thirds of the poverty threshold.

- Welfare workers had remarkable industry mobility. Over two-thirds shifted to a new industry sector during the 1990s. Most workers changing industries lost ground or maintained sub-poverty earnings. Welfare workers tend to be hired into growing industries with low-paid workforces. In these already low-paying industries there is an unusually large gap between earnings of welfare workers and the rest of the work force.

- African American workers living in high-poverty neighborhoods face especially difficult obstacles in finding sustained employment. Expanded housing opportunities, local job creation and transportation assistance will help more of these, and all low-wage workers, escape poverty.

- Many more welfare workers have the potential to lift their families out of poverty. We have at least three types of evidence that many workers have the potential to have greater success in the labor market than they have had so far under the GAIN program. First, 12 percent of workers entered high-wage jobs, then lost connection with regular employment and their earnings plummeted. These workers had the ability to land good jobs, but not the resources to hang on to them. Second, 17 percent of workers whose earnings were below the poverty threshold have levels of education, language skills and achievement test scores that are comparable to those of workers with above-poverty earnings. Third, 7 percent of workers had above-poverty earnings before GAIN and below-poverty earnings afterwards.

- Workers whose earnings trajectories lifted them out of poverty increased their average earnings by $128, or 22 percent, a quarter over each of the first ten quarters. Less than one-fifth of welfare workers were able to achieve this exceptionally strong upwards earnings trajectory that is required to escape the hold of poverty.

- Imposing a lifetime limit of five years on public assistance benefits is inconsistent with keeping many of the families studied in this report above the poverty threshold.

- The three inter-related factors of education, work history and type of industry that a worker is employed in explain nearly one-quarter of the differences in earnings among welfare workers. A single, English-speaking woman who completed two additional years of school and was able to move from a job with a temporary employment agency (where earnings of welfare workers average $468 a month) to a job in a medical clinic (where earnings of welfare workers average $1,130 a month) might see her annual earnings increase by $4,841. This increase is the sum of $970 for education ($485 for each of the two additional years of school) and $3,871 for moving into an industry that pays higher wages. These additional earnings would make the worker eligible for approximately $1,300 in additional Earned Income Tax Credits, for a total increase in annual income of $6,141.

- Following the 1990-1995 recession the Los Angeles economy shifted from a long-term post-war trajectory of sustained job growth to a trajectory that is yet to be defined. The region is seeing slow recovery from the recent recession, fewer jobs that pay living wages to people with average levels of education, and above-average rates of unemployed and discouraged workers. These worrisome indicators should be treated as a wake-up call for thoughtful efforts to protect and build on the region’s neglected economic strengths.

The increased rate of employment among welfare workers has increased economic output in Los Angeles County by half a billion dollars a year. Increasing the average earnings of 100,000 of these workers to the poverty threshold would increase economic output by another three-quarters of a billion dollars a year.

From a regional economic perspective the critical issue is whether the rate at which families exit poverty exceeds the rate at which they enter poverty. Reducing the total number of workers in sub-poverty jobs will help deflect the region from a low-wage growth path and increase the overall economic output of the region.

Recommendations

Six recommendations address actions by the County of Los Angeles. The seventh recommendation addresses a necessary action by the State of California.

- The Board of Supervisors of the County of Los Angeles should approve the action steps described below, identify organizations responsible for the actions, and hold those organizations accountable for successfully achieving the recommended outcomes.

- Annually review and readjust the allocation of family self-sufficiency funds based on the tangible contribution made by each program to increasing the rate of exits from poverty.

The evidence shows overwhelmingly that when welfare-to-work participants enter the labor market most do not earn enough to bring their families’ standard of living even close to the poverty threshold. The central problem in welfare-to-work is to make work pay enough to lift families out of poverty. Three types of solutions to this problem are needed.

- First, we need to improve the opportunities for workers to increase their earnings in the labor market.

- Second, we need to support welfare workers in achieving their highest potential in the workplace.

- Third, we need to strengthen the social infrastructure for addressing the survival needs of low-wage workers.

These approaches focus on enabling workers to survive autonomously.[4] The measure of success for these efforts should be their effectiveness in reducing the poverty rate among welfare workers.

The County of Los Angeles is to be commended for initiating and adopting the Long-Term Family Self-Sufficiency Plan. The plan reflects important insights into families’ needs for support and assistance as they attempt to leave welfare and become self-sufficient through work. The movement away from a Spartan work-first model and toward a human investment model for helping welfare recipients obtain sustaining employment is the key goal.

Our concern is that 39 percent of the $150.4 million in annual expenditures budgeted in the plan is for the delivery of ongoing social services that fall outside the autonomy-focused measures described above.[5] The most critical deficit in the plan is the virtual absence of allocations to support creation of sustaining jobs for welfare workers. In many ways this represents the current status of the county’s infrastructure for addressing the needs of the poor. The social service delivery system, both public and private, is more attuned to alleviating conditions associated with poverty than to equipping people to rise above poverty.

Social services are badly needed, but the $430 million in this fund was awarded to the county because of movement of welfare recipients into the work force. Accordingly, the highest priority for these funds should be increasing the self-sufficiency of welfare workers.

We can see the poor in terms of the problems they will have if they continue to be poor, or we can see them in terms of their possibilities for escaping poverty. The truth is that most people feel, think and act differently when they are not desperately poor. Many of this region’s poor parents are powerfully motivated to improve the lives of their families. A family self-sufficiency strategy that places greater emphasis on creating escape routes from poverty than on social services to ameliorate the dysfunctions caused by poverty will represent a more hopeful vision of possibilities for improving the lives of the poor.

It is our recommendation that the Family Self-Sufficiency Fund should be used to support an evolutionary process of building a community infrastructure for competently and effectively supporting upward economic mobility among low-wage workers. The primary elements should be:

- Increasing the supply of jobs that pay living wages;

- Strengthening workers’ skills and employment credentials through appropriate combinations of classroom education, vocational training, customized employer training, on-the-job training, and work experience; and

- Addressing the survival needs of low-wage workers by making childcare and health insurance permanently available, improving transportation services, and expanding the supply of affordable housing.

The funding allocations set forth in the plan should be reconsidered and readjusted annually based the emergence and competence of grassroots organizations for helping workers achieve self-sufficiency. Future funding decisions should be based on the tangible contributions made by each program to increasing the rate of exits from poverty.

3. Support growth of community-based economic development initiatives that combine grassroots affiliations with effective analytic capabilities.

When we look at the lives of specific individuals who need better jobs, all of the institutional fragmentation and blind spots that typify economic development programs are illuminated. A grassroots approach to economic empowerment opens possibilities for clear and comprehensive integration of program elements as well as credible and broadly accepted priorities for allocating program resources.

Looking at economic development outcomes throughout the United States, success stories are disappointingly scarce. Most communities have publicly funded economic development organizations, but what we typically see is:

- Business assistance activities that are driven by squeaky wheels rather than analysis of the comparative public benefits produced by different types of business growth.

- Absence of capabilities for analyzing public benefits other than sales and property taxes, little attention to public costs associated with different industries, and no attention to matching industry skill requirements with the occupational characteristics of local job seekers.

- High program costs per job created, and jobs that either are not accessible to entry-level workers or do not enable them to rise out of poverty.

- Outcomes among assisted businesses that are explained primarily by growth (or decline) in the regional economy and very little by economic development programs.

It is our assessment that sustained economic growth requires a coherent, comprehensible, and long-term vision that integrates five things:

- Informed participation and support of those who are to be benefited.

- Distinctive local attributes (including infrastructure, labor force, and industry base) that support neighborhood-level strategies.

- Economic development to provide opportunities for financial self-sufficiency.

- Social development to build full citizenship for all residents.

- Environmental and cultural preservation.

It is important to recognize that even within poor communities, the collective discretionary resources of local residents are likely to exceed public resources for economic development, housing improvement, or job training. Part of the answer for enabling communities that have received less-than-equitable shares of regional asset growth to become self-sustaining is to create symbols of hope and possibility that make it credible for individuals to believe in self investment and community investment. Another part of the answer is to increase access to resources that enable residents to invest in themselves.

A central premise is that economic development and family well being are closely connected, and by understanding specific workers we give coherence, legitimacy, pragmatism, and long-term viability to job creation initiatives.

Understanding and acting on highly specific and highly localized job creation opportunities requires both information and organizational capabilities that are not presently available. Most importantly, information and resources need to be provided at a neighborhood level and organized to support economic empowerment of local residents.

The Long-Term Family Self-Sufficiency Plan includes an allocation of $350,000 for community-based economic development activities in the first year of implementation. This modest amount should be greatly increased, using funds reprogrammed from other projects that fail to demonstrate a high level of effectiveness during the first year of implementation.

4. Retain and create jobs that pay sustaining wages through county, city and neighborhood-level job initiatives.

Governmental units with Los Angeles County need to develop the capability to produce a sound industrial development strategy and to act jointly on the strategy after it is produced. While it is beyond the resources and authority of regional institutions to control the course of the economy, it is reasonable to believe that they can provide slight but consistent nudges toward retaining and expanding industries that strengthen the economy and provide sustaining employment for local residents. Tools that the public sector can use include land use decisions, fee schedules, infrastructure improvements, expedited permit processing, nuanced application of environmental regulations, access to public financing tools, targeted job training, and industry forums that foster well-informed problem solving.

Most strategies for retaining and expanding industry sectors need to be implemented by regional, county and large-city units of government. Strategies for retaining, expanding, recruiting, or creating specific businesses that provide good jobs can be implemented at the city and community level. And many strategies for workforce development and creation of start-up businesses can be implemented at the community and neighborhood level. Job retention and creation strategies that correspond to the resources of different levels of governance are listed below. In every instance the focus of these strategies should be on creating new jobs in the regional economy rather than relocating jobs from neighboring communities.

Industry Strategies for Regional, County and City Implementation

- Broad support for target industries through land use policies, expedited permit processing, fee waivers, tax benefits, and infrastructure improvements.

- Reliable assurances about future regulatory requirements.

- Focused support for target industries through financial assistance, site assembly, redevelopment tools, master planned developments, work force training, and public-private forums for issue resolution.

- Formation and underwriting of research, development, marketing, and export services for consortia of small and medium size firms.

Employer Strategies for City and Community Implementation

- Assistance in recruiting, screening and training workers.

- Help finding space for expansion.

- Enterprise and revitalization zone benefits.

- Assistance with permits, licenses, inspections, and zoning.

- Business consulting services for improving manufacturing processes and products, and upgrading management systems.

- Support for new product development, re-tooling, and expansion.

Financial assistance.

Worker Strategies for Community and Neighborhood Implementation

- Career planning and development (appraisal, counseling, and planning).

- Targeted training and job placement programs.

- Post-employment support services.

- Advocacy and assistance in obtaining essential services such as child care and transportation.

- Coordinated job training and job creation programs.

- Linkages with organized labor and apprenticeship programs.

- Micro-enterprise loans and grants.

- Formation and support for worker-owned enterprises.

5. Ensure that welfare recipients who do not qualify for jobs that pay sustaining wages have individually-appropriate employment plans that integrate skill development and work activities.

This recommendation is already part of the Long-Term Family Self-Sufficiency plan but because of its importance and difficulty to implement we recommend that it be given special attention.

What we have learned about the difference in earnings among workers based on their skills, skill development experiences, work histories, and industry wage levels confirms the need to strengthen the welfare-to-work program by providing:

- Education and training that substantially strengthen workers’ skills and employment competencies;

- Employment experience that builds on skill development programs and provides entry to industries that pay living wages; and

- Supportive services that help workers stabilize their lives and meet the needs of both their children and their employers.

In order to provide effective assistance it is necessary to respond to welfare workers as individuals and develop individual employment plans that address each person’s needs and strengths. A realistic employment plan should take into account the individual’s aptitudes, skills, expressed interests, work history, personal circumstances, and conditions in the regional labor market. In this process:

- Physical and mental capacities, aptitudes and abilities tell what an individual can do.

- Interests and attitudes towards work tell what an individual wants to do.

- Work history tells what the individual has done.

- Labor market information identifies opportunities and requirements for work.

This information should be used to formulate an employment plan based on: (1) the range of jobs that are feasible for the individual, (2) real-world constraints in the labor market, (3) deficiencies in the worker’s skills or employment experience, and (4) needs for supportive services such as childcare and transportation.

The plan for most workers should include skill development through classroom or employer-based training and part-time employment that is linked to their skill development program. Depending on the skills of the worker, the part-time job might be one they find themselves or a subsidized job provided for them.

Some workers will require access to support services over a period of time that extends well beyond five years. Other workers who experience multiple entries and exits from the labor force and movement between employers will need repeated access to education, training and support services. Continuing and repeated services should be provided when needed.

6. Address the survival needs of low-wage workers by making childcare and health insurance permanently available, improving transportation services, and expanding the supply of affordable housing.

We recommend that in addition to the investments in job creation outlined above, the preponderance of expenditures from the Performance Incentive Trust Fund should be to expand programs that enable the working poor to survive autonomously above the poverty threshold. The core survival resources that should be continuously available to low-income welfare workers and others of the working poor who are eligible include:

- Childcare services.

- Health insurance.

- Affordable housing through mechanisms similar to the Section 8 program.

- Transportation assistance, including one-time costs to buy and insure a car.

7. The Governor of the State of California should direct the State Industrial Welfare Commission to review the current minimum wage and issue a wage order for California workers that establishes a minimum wage of at least $7.75 an hour. This new minimum wage should be pegged to the Consumer Price Index so that future adjustments occur automatically.

Raising the minimum wage will do more than any other single action to improve the situation of the working poor.[6] The real value of the minimum wage has fallen by over one-quarter since 1968. A worker employed full-time at California’s current minimum wage of $5.75 an hour will earn $11,500 a year. This is 86 percent of the 1999 poverty threshold of $13,423 for one parent with two children. Allowing for deductions of 13.45 percent of earnings for mandatory payroll taxes, a full-time worker needs to earn $7.75 an hour to have take-home earnings that lift a parent with two children above the poverty threshold.

Chapter Headings:

- Executive Summary and Recommendations

- Introduction

- Industry Restructuring, Migration and the Working Poor in Los Angeles

- The End of Welfare as We Know It

- Paths out of Poverty

- Finding Work and Earning a Living Wage

- Job Retention and Turnover

- Unstable Jobs: Welfare Workers in Precarious Labor Markets

- Diffusion of Workers Throughout the Economy

- Industry Mobility of Welfare Workers

- Industry Niches of Welfare Workers

- Local Labor Markets, Neighborhood Poverty and the Employment of Welfare Workers

- Conclusions

- Comments by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services and Economic Roundtable Responses

- Data Appendix

Index