Structural Inequity

Displacement of brick-and-mortar retail stores by online retailing and sprawling warehouses is coming at the cost of climate change, bad air, low wages, and extreme disparities between neighborhoods where consumer goods are warehoused and neighborhoods that can afford to buy the goods.

In each of the past three decades, 175 million more square feet warehouse space has been built in the four Southern California counties of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino. Each new warehouse has increased diesel truck emissions in working class neighborhoods where frontline warehouse workers earn median annual wages of $25,154.

Petroleum waste products produced by moving consumer goods from the seaports to warehouses, and then from warehouses to affluent homes, are released into the air we all breathe. But pollutants are most heavily concentrated in the neighborhoods of low-wage warehouse workers.

Battery-electric trucks will eliminate six million tons of emissions a year in these four counties and create good jobs in the electricity sector, unless California’s mandate for clean trucks is derailed by utility district delays in providing electricity.

Neighborhoods with Warehouses

Neighborhoods with Warehouses

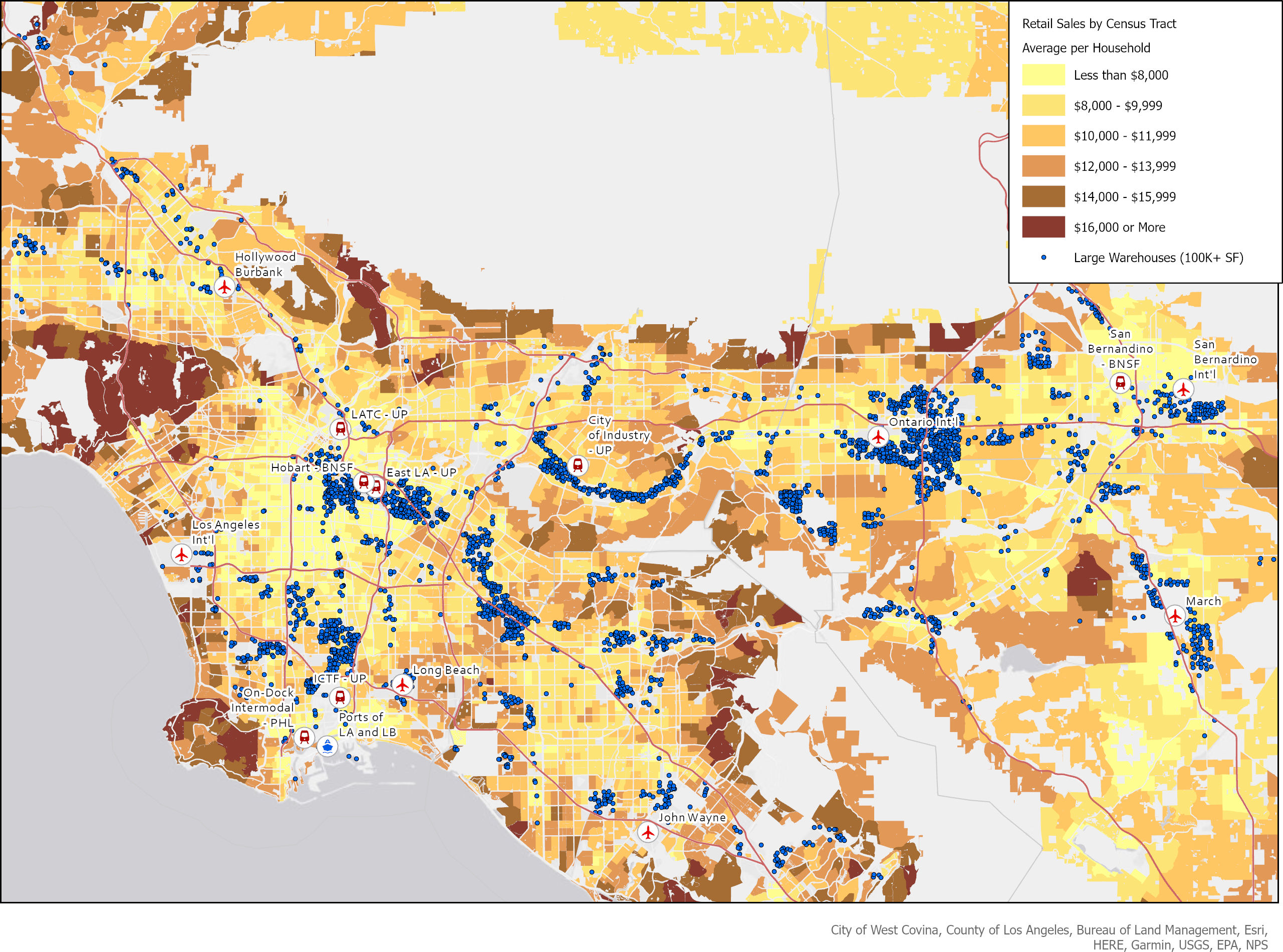

Warehouses and the workers employed in them are located in lower income communities. The consumers that benefit most from the logistics sector are higher-income communities, far-removed from the noise and emissions caused by diesel trucks and warehouses. There is fundamental environmental and economic inequity between the neighborhoods that do the heavy lifting of the logistics system and the neighborhoods that benefit.

There are over 3,300 warehouses with 100,000 or more square feet of space each in the four county region. They cover over 800 million square feet and bring in over $6 billion a year in revenue. With smaller warehouses added in, the total space is more than one billion square feet.

Recent warehouse construction is concentrated in San Bernardino County, where low land costs offset the distance from retail stores, consumer neighborhoods, and the San Pedro Bay Ports.

Drayage Trucking Companies and Drivers

Drayage Trucking Companies and Drivers

Drayage companies, which make short-haul trips with heavy cargo, are concentrated near the San Pedro Bay Ports, with secondary concentrations in the Inland Empire. Most truck drivers live near these trucking companies. Their livelihoods expose them to the emissions and noise of diesel trucks when they are working, and often these impacts are also part of the after-work environment in their neighborhoods.

Two-thirds of trucking companies are small businesses with nine or fewer trucks. However, large corporate trucking companies dominate the industry. Companies with 125 or more trucks own 95 percent of the trucks that move cargo into and out of the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

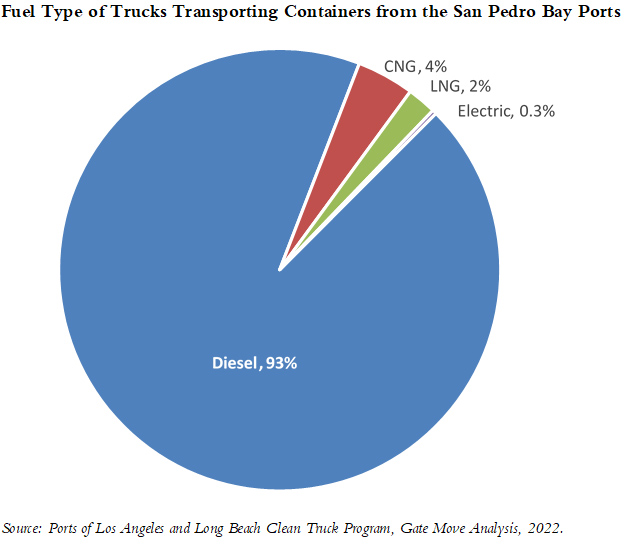

Diesel trucks have the second highest greenhouse gas emissions per ton-mile of any mode to cargo movement, exceeded only by cargo aircraft. Their high greenhouse emissions and wide deployment make them a significant contributor to climate change.

Deploying Electric Trucks

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) and South Coast Air Quality Management District (AQMD) have mandated a rapid transition to clean truck propulsion technology.

Beginning January 1, 2024, CARB is requiring all new drayage trucks entering seaports and intermodal railyards to be electric. Diesel trucks that that are registered with the state before the end of 2023 can remain in operation until 2035. This is the Advanced Clean Trucks Rule.

There is strong opposition to this regulation by trucking companies. Nineteen states are seeking appellate court review in a challenge to the Environmental Protection Agency waiver granted for California’s Advanced Clean Trucks Rule.

Similarly, the California Trucking Association is challenging the AQMD rule that makes warehouses accountable for emissions from diesel trucks delivering cargo to and from warehouses in the district.

Eight heavy-duty truck manufacturers have initiated small-scale manufacturing and sales for zero-emission, battery-electric tractors. Most currently available heavy duty electric trucks are capable of meeting basic performance requirements for short-range drayage operations, roughly up to 175 miles between charges. This means that current battery-electric models are restricted to short-hauls or lighter-weight drayage tasks.

Eight heavy-duty truck manufacturers have initiated small-scale manufacturing and sales for zero-emission, battery-electric tractors. Most currently available heavy duty electric trucks are capable of meeting basic performance requirements for short-range drayage operations, roughly up to 175 miles between charges. This means that current battery-electric models are restricted to short-hauls or lighter-weight drayage tasks.

There is strong year-over-year progress in the robustness and capabilities of zero-emission trucks. The capabilities and reliability of electric trucks will continue to improve and in the coming years they will be able to perform all drayage functions currently performed by diesel trucks.

Given the current low-volume of electric truck sales, the purchase subsidies available in California are currently sufficient to reduce their cost to less than the cost for a diesel truck. However, there are only enough subsidy funds to cover a small fraction of the zero-emission trucks that must be put in service by 2035. As sales ramp up, there will be an interval when subsidies are scarce and the cost of electric trucks has not come down to the cost for diesel trucks.

The current subsidy programs prioritize small truck fleets, but truck dealerships report that small operators are overwhelmed by the paperwork and documentation required to obtain subsidies, and often abandon the effort to obtain a subsidy as well as to buy an electric truck.

In the interest of equity, it is important to continue prioritizing small fleets for subsidies and also to streamline the application process and provide user-friendly technical assistance for small fleet owners seeking subsidies.

Electricity for Charging Stations

Electricity for Charging Stations

Electric truck dealers and fleet operators have identified delays in obtaining electric power for charging stations as the most serious obstacle for deploying electric trucks.

The supply of electricity to recharge battery-electric trucks is lagging the timetable set by California Air Resources Board for the transition to zero-emission drayage. Utility districts will be a bottleneck unless they act proactively to build the electrical distribution infrastructure required to support clean trucking.

Impacts of Warehouse Trucking

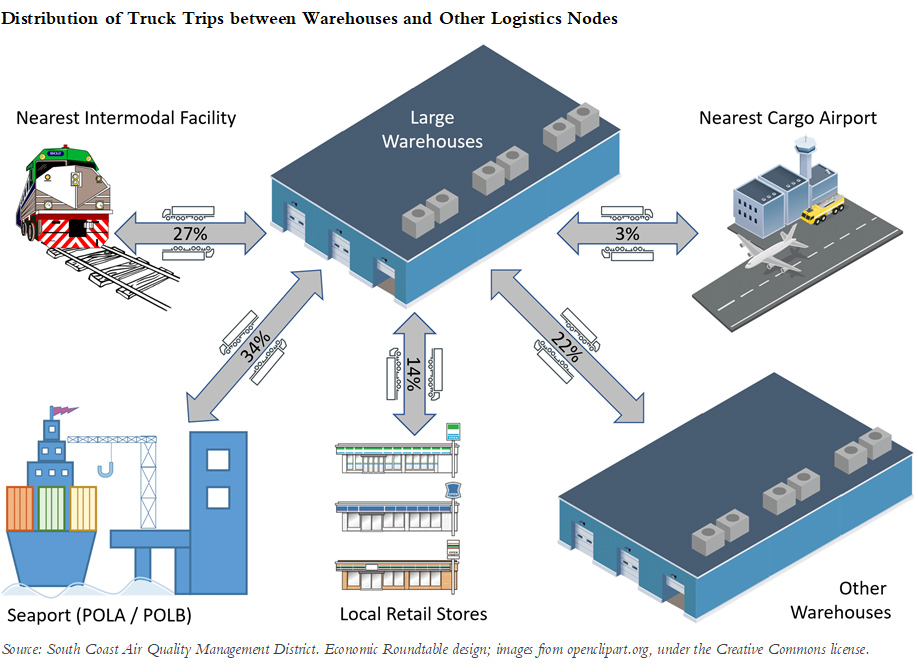

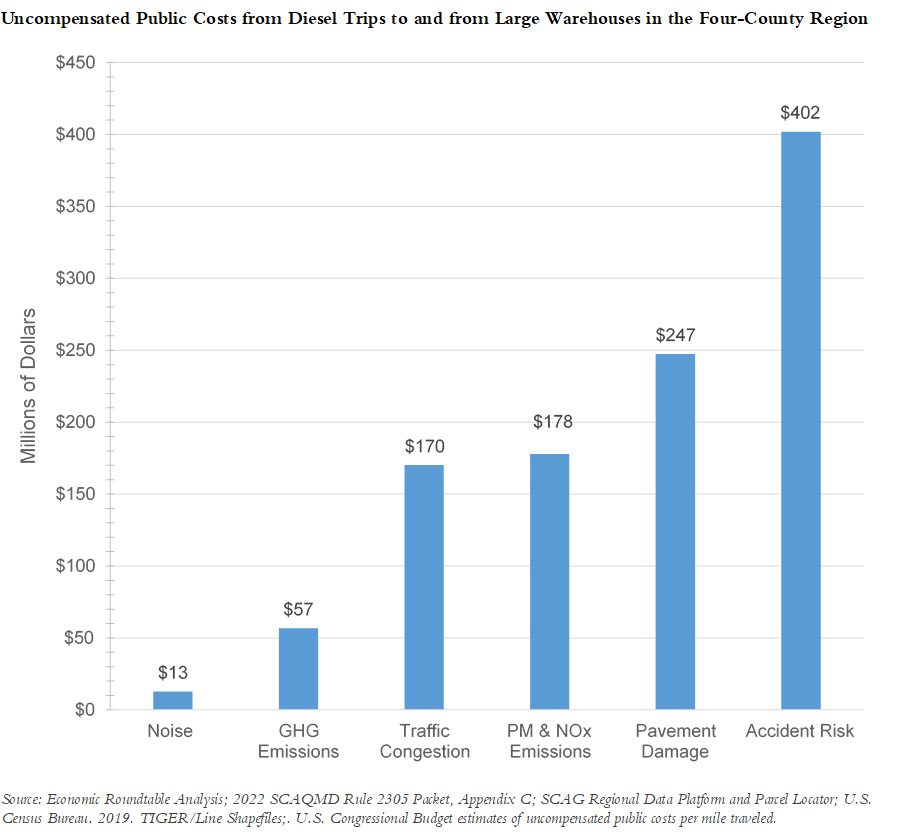

Diesel trucks travel over 415 million miles a year to and from large warehouses in the four-county region. There are $1 billion in annual uncompensated public costs from wear and tear on roads and bridges; delays caused by traffic congestion; injuries, fatalities, and property damage from accidents; and harmful effects from exhaust. California ranks 46th among the 50 states in the share of roads that are in acceptable condition.

The 11 million annual heavy-truck trips produce almost six million tons of greenhouse gases that accelerate global warming. They also produce 1,161 tons of nitrogen oxides, which can irritate sensory organs, and cause shortness of breath with fluid build-up in the lungs. And they produce 29 tons of fine particulate matter, which causes bronchitis and asthma attacks.

The annual health costs for residents from current diesel truck emissions, and, conversely, the health benefits from having electric trucks move cargo instead of diesel trucks are an estimated $166 million a year.

Jobs in the Electricity Sector

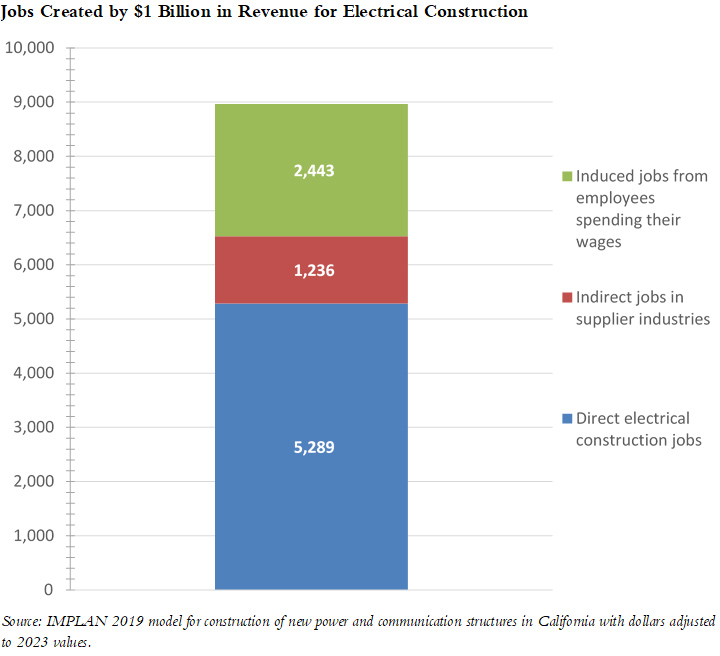

One job is created for every $111,512 spent on the electrical infrastructure required to recharge electric trucks. This includes jobs building electrical utility infrastructure and installing electrical wiring and equipment to charge trucks, as well as jobs in industries that provide supplies and services for electrical construction, and additional jobs that are created when workers in electrical construction and supplier industries spend their wages.

The electricity sector provides high-pay, living-wage jobs. The average hourly wage for frontline electrical construction is $35 an hour.

Higher Skills but Lower Pay for Warehouse Workers

The introduction of new technology in warehouses and the rapid turnover of goods has increased the skill requirements for frontline warehouse jobs. However, the wages paid to warehouse workers have decreased.

The average wage in 2022 for warehouse workers in frontline occupations was $18.95 an hour. This is less than half of a living wage.

The jobs to electrify the logistics chain that brings goods to warehouses are much better than the jobs inside warehouses. This includes jobs expanding the electrical transmission infrastructure, building recharging station for electric trucks and installing solar panels at warehouses.

Impacts of Warehouses on Frontline Families

There are just under 365,000 residential parcels located within 2,000 feet of large warehouses, across the four-county region. Three-quarters are single-family homes, and another quarter are multi-family properties. This housing provides homes for over 2.1 million residents.

Warehouses and the linked trucking and air cargo networks degrade the habitability of neighborhoods. Factors that diminish the desirability of housing in these neighborhoods include freeways, heavy traffic, truck-train intermodal facilities, cargo airports, truck depots, and warehouses.

Warehouses and the linked trucking and air cargo networks degrade the habitability of neighborhoods. Factors that diminish the desirability of housing in these neighborhoods include freeways, heavy traffic, truck-train intermodal facilities, cargo airports, truck depots, and warehouses.

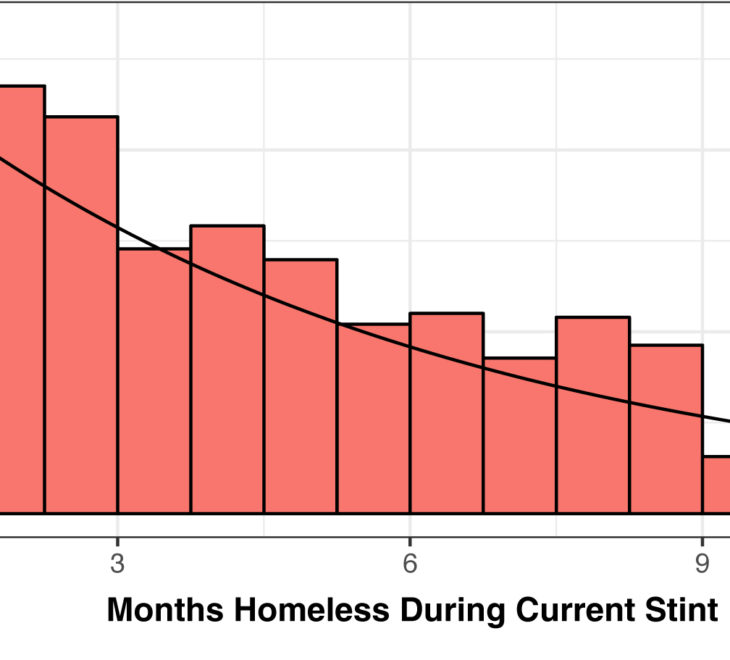

Families living near large warehouses experience an elevated likelihood of poverty throughout the four-county region. In addition to economic distress, these families suffer from traffic noise and congestion, as well as long-term exposure to air pollution, that make it difficult to get the peace, quiet and cleaner air needed for a healthy life.

The median income within a 2,000-foot perimeter of large warehouses is 18 percent lower than in the rest of the four-county region, and the poverty rate is 22 percent higher than outside the perimeter.

Many families live near warehouses out of economic necessity, settling on less desirable neighborhoods where rent is lower. Even with lower rent, many families cannot afford housing that meets minimum standards of space and privacy for household members. They often rent a smaller unit where more than one person is crowded into each room in order to reduce the rent. The rate of overcrowded housing is 38 percent higher within the 2,000 perimeter of large warehouses than in the region a whole.

Households living within 2,000 feet of a large warehouse are 10 percent more likely to have children, 23 percent more likely to be headed by a female, and 40 percent more likely to be Latino than in the overall region.

Respiratory Distress

Respiratory Distress

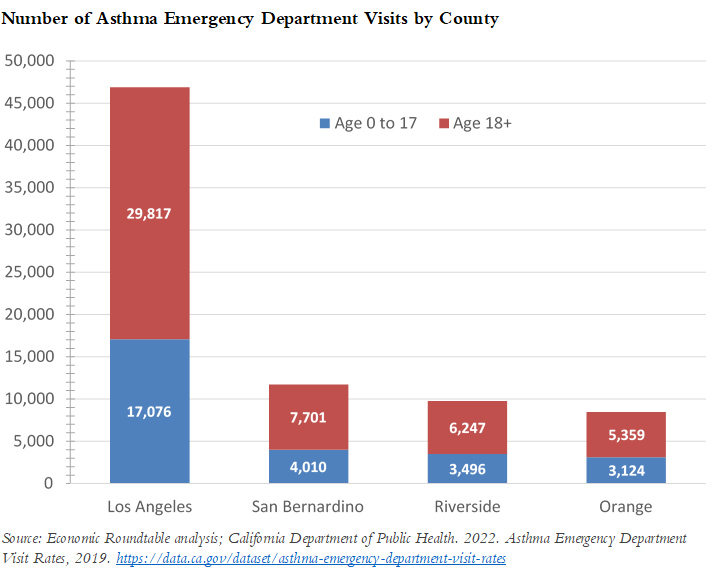

The direct pollutants from diesel truck trips to and from large warehouses, cause elevated rates of respiratory distress. This is compounded by the indirect pollutants attributable to the electricity and natural gas that these buildings consume onsite.

Large swaths of the Inland Empire are in the highest quintile of the pollution burden index, meaning they have the highest exposure to criteria air pollutants, including ground level ozone, carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and particulate matter.

Homes near the large warehouse clusters by Ontario International Airport and San Bernardino International Airport breath air with the highest level of fine particulate matter, increasing risks of asthma and heart disease.

The rate of emergency department visits for asthma attacks reflects the location of manufacturing and logistics land uses. South Los Angeles, City of Industry, Ontario and San Bernardino have elevated rates of emergency department visits as well as the largest concentrations of logistics activity.

Recommendations

- Equitably assess the full environmental and economic impacts of warehouses before approving any new warehouse construction or the expansion of air cargo facilities.

- Fully enforce noise regulations for all warehouses.

- Establish a living minimum wage for warehouse workers.

- Protect the truck electrification timeline created by the Advanced Clean Fleets Regulation and the Warehouse Indirect Source Rule.

- Proactively upgrade the electrical networks serving trucking companies and warehouses to ensure that electricity is available to recharge trucks as soon as it is needed.

- Enact rules requiring the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to provide technical and financial assistance for installing commercial recharging stations.

- Safeguard electric subsidy funds to ensure ongoing support for small trucking companies after demand grows and subsidy funds shrink.

Press Coverage

A Just Transition For Southern California

Paul Rosenberg, Random Lengths News (September 28, 2023)

Reports claim trucks tied to warehousing are fueling inequality in SoCal

Anthony Victoria, KVCR News (September 28, 2023)

New reports link warehouse boom to economic and environmental disparities in Southern California

Christopher Salazar, The Frontline Observer (September 28, 2023)