Welfare reform raises the prickly question of what mix of understanding, support and pragmatic pressure is needed to move welfare recipients into employment. Many workers are scrambling to keep the wolf from their own doors in the face of industry restructuring, rapid technological change, and intense pressures to increase corporate profits. In this highly competitive environment, workers are continually struggling to adapt and increase productivity because their survival is at stake. They might well ask whether welfare recipients deserve different treatment. At the same time, common sense and first hand experience tell us that most people are on welfare because of extreme life adversities, many have below-average skills, and Los Angeles County still has 5 percent fewer jobs than in 1990, even though the population has grown by five percent. Regardless of how we view welfare dependency, the reality is that a majority of aid recipients do work and are part of the low-wage workforce. We share an important practical interest in seeing welfare recipients successfully employed because the social fabric of the region will be damaged in ways that affect everyone if attempts at welfare reform leave us with increasing numbers of destitute families.

Welfare reform raises the prickly question of what mix of understanding, support and pragmatic pressure is needed to move welfare recipients into employment. Many workers are scrambling to keep the wolf from their own doors in the face of industry restructuring, rapid technological change, and intense pressures to increase corporate profits. In this highly competitive environment, workers are continually struggling to adapt and increase productivity because their survival is at stake. They might well ask whether welfare recipients deserve different treatment. At the same time, common sense and first hand experience tell us that most people are on welfare because of extreme life adversities, many have below-average skills, and Los Angeles County still has 5 percent fewer jobs than in 1990, even though the population has grown by five percent. Regardless of how we view welfare dependency, the reality is that a majority of aid recipients do work and are part of the low-wage workforce. We share an important practical interest in seeing welfare recipients successfully employed because the social fabric of the region will be damaged in ways that affect everyone if attempts at welfare reform leave us with increasing numbers of destitute families.

The nation’s best known welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was created to give widows and destitute mothers the means to stay at home and care for children. However, the entry of large numbers of American mothers into the paid workforce has created increasing tension between the desire to care for impoverished children and the belief that able-bodied parents should earn their own living. Recent federal legislation has replaced AFDC with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). California enacted CalWorks to implement this new federal block grant program, placing a five-year lifetime limit on aid for adults. Months in which the mother receives any part of her income from TANF count toward her lifetime five-year limit, making it critically important for welfare recipients to find stable, full-time employment that pays a living wage.

The purpose of this report is to provide practical, objective information that will help policy makers and program administrators create successful welfare-to-work programs in Los Angeles County, which has the nation’s largest public assistance caseload.

One of the challenges in preparing a report on economic and employment characteristics of welfare recipients is that the actual make-up of the welfare population changes from month-to-month and there is a dearth of information about occupations in which aid recipients are employed. The size and makeup of the welfare caseload is an artifact of the county’s demography, economy and social conditions, and all of these factors change continuously. The core research strategy for this report was to use Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) data for Los Angeles County from the 1990 U.S. Census to identify occupations, industries and work-related characteristics of the day-to-day caseload of aid recipients, and then to update this information with current labor market data.

Profile of Aid Recipients

There is more variation in work history and education within the aid population than there is between recipients and the general workforce. For example, while 22 percent had an eighth grade education or less, 24 percent had at least some college, and while 24 percent had never worked, 26 percent were working in 1990. Important characteristics of the county’s aid caseload include:

- Over three-quarters of aid recipients’ earnings appear to come from jobs that do not provide legally mandated employee benefits such as Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, or Disability Insurance, much less health care coverage. This suggests that after exhausting their five-year maximum allotment of benefits, many former aid recipients may find themselves without the social protections afforded most American workers.

- Most working aid recipients need a car to commute to their jobs, manage the logistics of getting children to and from child care, and deal with other household needs such as groceries, laundry, and visits to medical clinics. Access to reliable, affordable transportation is likely to be a significant barrier to finding and keeping jobs for many aid recipients in the county.

- The average working aid recipient is employed for the annual equivalent of a half-time job. Finding long-term, full-time employment is fully as important and difficult as finding jobs that pay a living wage for aid recipients making the transition from welfare to work.

- Even among those receiving aid benefits, many families had difficulty surviving. Roughly one-half were sometimes unable to pay their rent on time, one-quarter sometimes did not have enough food for themselves and their children, one-quarter had limiting health conditions.

- Many aid recipients were actively trying to improve their life situation. One-quarter were attending school to improve their skills.

Comparing Single Mothers With and Without Aid

A fundamental difference between single mothers who are part of the welfare caseload and those who are not receiving aid is their educational attainment. Among non-recipients, only one-third do not have a high-school diploma, while among those receiving aid over half had not completed high school. About 44 percent of the non-recipients had at least some college-level education, while only half as many mothers receiving assistance had attended college.

A principal difference between many low-income single mothers surviving without aid and those receiving aid is the level of financial assistance they receive from other household members. The additional adults in non-aided households tended to have higher incomes and also, there were more of them per household with incomes compared to households with public assistance. Other significant differences between single mothers who were receiving public assistance with those not receiving assistance include:

- Only about 30 percent of single mothers receiving public aid were participating in the labor force in 1990 — that is, either working or actively looking for work. A full 80 percent of non-recipient mothers were active in the labor force.

- Only 16 percent of the aid recipients in the county caseload were employed, while three-fourths of the non-aid group worked at the time of the 1990 Census.

- Over 85 percent of the income of single mothers not receiving aid comes from their jobs, while for aid recipients over 84 percent of their income comes from public grants. The overall average-annual income received by non-recipients is double that of those receiving aid.

Work-Readiness Groups Among Aid Recipients

The central question raised by impending welfare reform is, what works for moving very poor people into steady employment? A look at actual characteristics of different work-readiness groups within the welfare caseload provides a practical basis for designing programs that will help welfare recipients survive in the labor market.

About one-fifth of the county’s caseload of single mothers were employed at the time of the Census, and had significant earnings (earning half or more of their total income), indicating that they had viable prospects for economic self-sufficiency. Another fifth were employed or had been employed in the past two years, but did not have significant earnings, indicating intermediate prospects for self-sufficiency for this group. And about three-fifths of the county’s caseload had not worked recently or had never worked, indicating difficult prospects for self-sufficiency.

Each of these three work-readiness groups was further divided into two subgroups: aid recipients born inside the United States, and those born abroad.

- Within each work-readiness group, recipients born in the United States were further removed from poverty than those born abroad.

- Those born abroad worked more hours at about three-quarters the hourly wage and for about four-fifths the average-annual income of their U.S.-born counterparts.

- Among recipients born in the U.S., higher levels of education were strongly associated with better labor market connections. The connection between education and successful employment was much weaker among recipients born abroad, most of whom lacked high school diplomas.

- The ability to speak English well or very well and eight or more years spent in the United States were predictors of stronger labor market connections among recipients born abroad.

- Within each ethnic group, mothers with at least a high school diploma had stronger labor market attachments than those without a high school diploma. However, Anglos and Latinas benefited more from a high school education than did Blacks. Among women with just a high school diploma, 31 percent of Anglos, 25 percent of Latinas, and only 16 percent of Blacks had significant earnings.

- Forty-eight percent of mothers receiving aid in Los Angeles County spoke a language other than English at home. Women with little or no English-speaking ability had weak labor market connections, and when they found jobs it was most likely as cleaners or sewing machine operators.

- Higher earnings among welfare workers tended to be the result of more hours worked as opposed to being in better-paying occupations than those held by welfare workers with lower earnings, suggesting a ceiling on possible earnings and prospects for self-sufficiency unless workers gain access to better occupations.

- Characteristics that predict improved prospects for employment and economic self-sufficiency, and that can be used to identify groups of aid recipients with different levels of need for training and supportive services, include: education, ability to speak English, number of children, age of children, work history, length of time since last job, occupation, and presence of other adults in the household who contribute income or assistance in caring for children.

Managing both Work and Parenting in Low Wage Jobs

A study of welfare workers in Los Angeles found that part of the reason why many recipients are unable to achieve economic self-sufficiency lies in the difficulty of combining parenting with work performed outside the home, especially for low-skilled workers. Most welfare recipients find employment in the low-wage labor market, and these jobs seldom offer workplace supports that reconcile competing demands of motherhood and paid labor. Without adequate childcare and transportation, and without enough money to purchase private services, even the most stable jobs obtained by welfare recipients are likely to be short-lived.

Childcare arrangements among working welfare mothers are often unreliable, inconsistent, and “make-shift.” In part, this is because low-skilled jobs often have unpredictable hours, and it is difficult to arrange a regular childcare situation for a job that does not have a consistent schedule. In addition, because they do not have enough money to purchase reliable, professional childcare services, low-income mothers often seek these services from other low-income mothers, who face many of the same work and family demands as the mothers of the children in their care.

The Los Angeles Labor Market

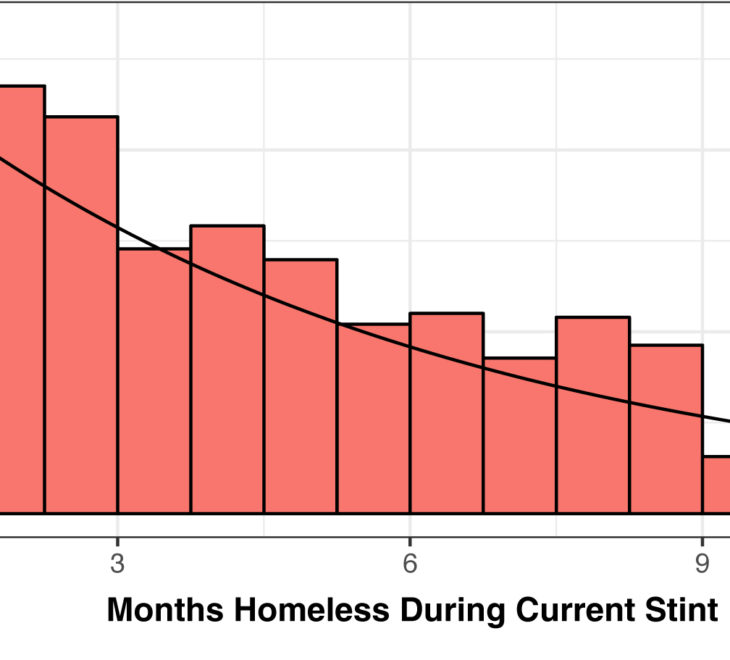

The decision to implement a major change in the administration of county welfare programs in California has come at the end of the most serious loss in employment in Los Angeles since the 1930s. Between 1990 and 1994, Los Angeles County lost 10 percent of its wage-and-salary jobs. One result was a substantial increase in the level of unemployment.

Historical labor force and welfare caseload data demonstrate a strong relationship between the number of jobs available that can support a family and the number of families that can support themselves. This is reflected in a direct correlation between changes in employment and changes in welfare caseloads in Los Angeles.

- Los Angeles County lost 436,700, or 10 percent, of its jobs between 1990 and 1994; by 1997 it had regained only 168,800 of these jobs.

- Despite the beginnings of an economic recovery, unemployment in Los Angeles County still averages close to 300,000.

- Because of the large number of discouraged workers, the true level of unemployment may well be as much as 200,000 to 300,000 higher than the official unemployment figure for Los Angeles County. This means that the actual current unemployment rate could be approximately 10.5 percent.

Jobs in Which Aid Recipients Find Work

Over the past five years, Los Angeles County’s primary employment program for aid recipients, GAIN, has utilized a strategy called “Jobs First” that attempts to quickly move recipients into employment while minimizing time and money spent on skill development. Because of the emphasis on immediate employment, it is likely that many aid recipients are returning to the same jobs in which they previously worked. Occupations that are typical sources of employment for welfare workers were investigated to assess whether they offer prospects for stable, family-supporting jobs.

- Average weekly earnings of aid recipients as a percent of average weekly earnings of all workers in the same occupation ranged from a low of 40 percent for nursing aides and orderlies, to a high of 88 percent for sales workers.

- The average weekly hours worked per week by aid recipients as a percent of hours worked by all workers ranged from a low of 55 percent for sales supervisors and proprietors, to a high of 82 percent for janitors and cleaners.

- An average of one in four non-welfare workers and job seekers in occupations that employ large numbers of welfare workers had incomes below the poverty level.

Job Outlook for Aid Recipients

Two approaches were used to evaluate constraints facing adult welfare recipients seeking regular employment that will adequately support their families without welfare grants. The first examined employment trends in occupations in which welfare recipients have worked in the past. The second examined employment trends and wage rates in occupations that require one year or less of training, and which tend to match the training and education of most adults receiving welfare.

- Employment data for occupations in which welfare recipients have experience show that between 1990 and 1994, there was a sharp decline of 315,700 jobs in the county. A recovery of 61,000 of these jobs occurred between 1994 and 1996. Projections anticipate an average gain of 67,800 jobs per year in these occupations between 1996 and 1999.

- Over the next two years there will be an average of 2.5 welfare-adult job seekers for every new net job opening expected to be created per year in Los Angeles County for occupations in which welfare recipients have experience. This estimate does not include other unemployed job seekers in the county.

- Adding the estimate of potential welfare-adult job seekers to the total number of unemployed workers in county results in a ratio of 5.4 job seekers for every new job opening within occupations in which welfare recipients have had experience. This ratio does not incorporate the considerable number of discouraged workers in the county.

- Among occupations appropriate for most welfare adults, three-fourths of the projected annual job openings offered new job applicants a median wage of $6.99 per hour or less. Nineteen percent of these projected openings were estimated to pay $7.00 to $9.99, and 1.3 percent paid $10 and over $10.00 per hour.

Recommendations

Employment of welfare recipients depends upon, and in turn will influence, the future growth path of the Los Angeles economy. The industrial structure and vitality of the region will determine the level of demand and type of work available for aid recipients. And in turn, the quality and availability of workers will influence the growth of industries in the region and type of new job opportunities that are created. Employment of aid recipients and growth of the economy to provide adequate job opportunities are linked developmental challenges for the Los Angeles region.

The goal of enabling all potential workers to put their skills to productive use in building a viable economy can be a unifying vision that informs and gives common purpose to public sector policy makers, welfare administrators, education, job training and supportive service organizations, and economic development professionals. Coordinated investments in worker skills, employment services, economic development, and job creation can yield high dividends through reduced social dependence and a stronger regional economy.

Employment-Related Services for Each Work-Readiness Group

Significant investments in skill development and access to new, better-paid occupations are needed to enable most recipients in the county’s welfare caseload to become financially self-sufficient before their five-year lifetime limit on aid benefits is exhausted. Successful employment and financial self-sufficiency are dependent upon having a number of skills and resources. Important factors that should be used in determining the work-readiness of aid recipients include:

- Education

- Ability to speak English

- Age of children

- Work history

- Length of time since last job

- Occupation

- Access to vehicle to get to work

- Other helping adults in the household

- Length of time on welfare

Individual assessment of participants’ work-readiness is likely to result in modifying past practices under the county’s GAIN program, with less emphasis placed on immediate full time employment for most recipients, and more emphasis placed on a balanced mix of part-time work, schooling and job training.

Individuals who are ready to search for a job should receive career counseling and job search assistance that effectively supports their re-entry into the labor market. Counseling should steer job seekers away from occupations that offer bleak prospects for financial survival. Work-related activities and services need to be tailored to the needs of each work-readiness group. The overall menu of needed services and activities includes:

Job search and placement

Full-time employment

Part-time employment

Subsidized employment

Work tools and clothes

Education

English language training

Job skills training

Childcare

Transportation assistance

Economic Development and Job Creation

One of the fundamental problems facing welfare workers in Los Angeles is the shortage of jobs, particularly jobs offering full-time, year-round employment. Economic development and job creation should be targeted on industries that will both hire welfare workers and provide opportunities to earn family-supporting incomes. Economic development projects should be based on analysis of the skill characteristics of available workers as well as the strengths of specific localities for business attraction and expansion. Economic development and job creation strategies that are needed to employ Los Angeles County’s welfare workforce include:

- Retain and expand businesses in urban centers by facilitating capital access and partnerships with the corporate and university sectors.

- Develop nonprofit business enterprises through technical assistance and capital for expansion.

- Fund the California Infrastructure Bank.

- Target investment of public sector retirement fund assets for local economic development.

- Establish a secondary market for state and local economic development revolving loan funds, similar to Fannie Mae, to increase the amount of capital available to small businesses.

- Streamline and maximize business incentives for local economic development and package them into customized, flexible “bundles” for targeted industries.

- Use private or nonprofit agencies as temporary employment agencies to place and support welfare workers.

- Create public service jobs.

- Provide subsidized work to build work experience and job skills for recipients without work histories.

- Provide improved local labor market and industrial base information.

Long-Term Strategies for Welfare Financing

At both the county and state levels an analysis should be made of the feasibility of severing portions of local and state funds for welfare from federal TANF funds to create a longer-term income maintenance program for individuals who are unlikely to achieve economic self-sufficiency within the time limits set by TANF.

Conclusion

It is beneficial for people who are able to work to have employment. Work offers dignity, standing in society, human relationships individuals otherwise would not have, and possibilities for an improved standard of living. At the same time, the Los Angeles region does not have enough jobs for everyone who needs work, and significant gains in both the carrying capacity of the local economy and the skill levels of aid recipients are needed to provide adequate opportunities for economic self-sufficiency. The need for a stronger economy and an expanding labor force of skilled, productive workers can provide a unifying vision for growth of the Los Angeles region.

Chapter Headings

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Approach to Understanding Jobs of Aid Recipients

- Profile of Aid Recipients

- Comparison of Single Mothers With and Without Aid

- Work-Readiness Groups Among Aid Recipients

- External Demands on Low Wage Workers

- Welfare Recipients and the Los Angeles Labor Market

- Occupations and Industries Employing Aid Recipients

- Job Outlook for Aid Recipients

- Policy Recommendations

- Statistical Appendix