Executive Summary

The central question investigated in this study is the public costs for people in supportive housing compared to similar people that are homeless. The typical public cost for residents in supportive housing is $605 a month. The typical public cost for similar homeless persons is $2,897, five-times greater than their counterparts that are housed. This remarkable finding demonstrates that practical, tangible public benefits result from providing supportive housing for vulnerable homeless individuals. The stabilizing effect of housing plus supportive care is demonstrated by a 79 percent reduction in public costs for these residents.

The study encompasses 10,193 homeless individuals in Los Angeles County, 9,186 who experienced homelessness while receiving General Relief public assistance and 1,007 who exited homeless by entering supportive housing. Two different methods were used to independently verify changes in public costs when individuals are housed compared to months when they are homeless. There are six bottom line findings:

- Public costs go down when individuals are no longer homeless

- 79 percent for chronically homeless, disabled individuals in supportive housing

- 50 percent for the entire population of homeless General Relief recipients when individuals move temporarily or permanently out of homelessness

- 19 percent for individuals with serious problems – jail histories and substance abuse issues – who received only minimal assistance in the form of temporary housing

- Public costs for homeless individuals vary widely depending on their attributes. Young single adults 18 to 29 years of age with no jail history, no substance abuse problems or mental illness, who are not disabled cost an aver¬age of $406 a month. Older single adults 46 or more years of age with co-occurrent substance abuse and mental illness, and no recent employment history cost an average of $5,038 a month. A range of solutions is required that match the needs of different groups in the homeless population.

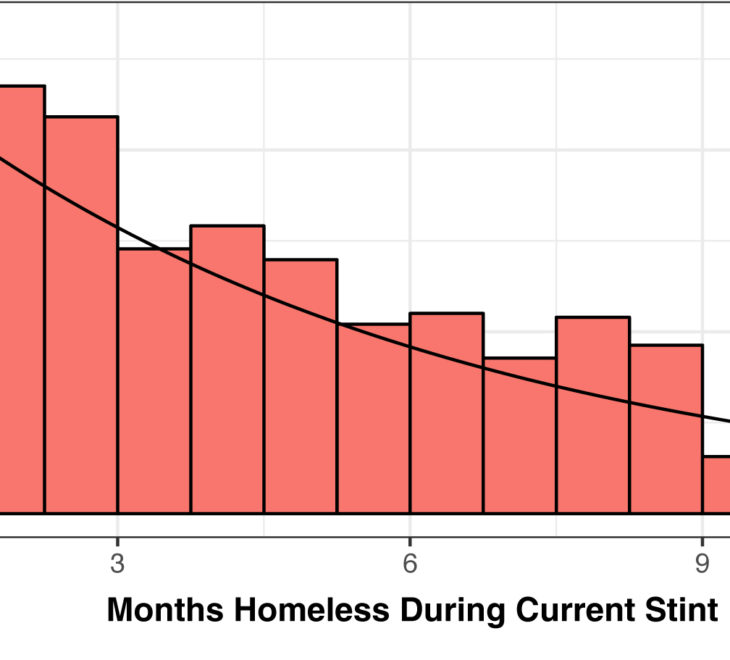

- Public costs increase as homeless individuals grow older. There is a strong case for intervening early rather than deferring substantive help until problems become acute.

- Most savings in public costs come from reductions in health care outlays – 69 percent of the savings for supportive housing residents are in reduced costs for hospitals, emergency rooms, clinics, mental health, and public health.

- Higher levels of service for high-need individuals result in higher cost savings, as shown by the much higher savings from supportive housing compared to temporary housing, and by the higher saving for supportive housing residents in service-rich environments.

- One of the challenges in addressing homelessness is housing retention – keeping individuals who may well be socially isolated, mentally ill and addicted from abandoning housing that has been provided for them.

Recommended Solutions

Link housing strategies to cost savings – The cost map for single homeless adults developed through this study can guide cost effective housing strategies.

Strengthen government-housing partnerships and leverage resources – It is difficult to convert cost savings of hospitals and other public agencies into cash that can be reallocated to underwrite supportive housing because the demand for these agencies’ services often exceeds the number of people they can serve. The homeless person who is not served may simply open up a hospital bed for another sick person. However, there is a powerful public interest in housing homeless persons and reducing the public costs for crises in their lives. It is critically important to expand the role of public agencies in providing on-site services for supportive housing, including mental health and drug and alcohol services, and SSI advocacy. It is also critically important to use available funds, such as General Relief, to house more homeless people.

Improve retention rates for individuals in supportive housing – Supportive housing organizations need public help in providing higher levels of on-site services to improve housing retention rates. Individuals with above-average risks of leaving housing include those that have co-occurrent mental health and substance abuse problems, those with jail histories, and young adults.

Increase the supply of supportive housing – Los Angeles County has far less supportive housing than is needed to shelter its disabled homeless population. This housing inventory can be expanded through new construction, master leases, and scattered site rentals. All three approaches need to be expanded. There is a window of opportunity for affordable master leases in the currently less expensive housing market.

Produce information for developing comprehensive strategies and improving outcomes – Los Angeles needs to get its arms around its homeless residents by getting enough information to understand who they are and what they require, and by acting on that information to provide shelter. This includes the size and composition of the population, cycles and duration of homelessness, family and immigrant homelessness, and outcomes for those who leave housing.

Background of this Study

“The Chronic Homeless Initiative

In 2003, Los Angeles was one of eleven jurisdictions awarded grant funding for a new federal Initiative. Coordinated by the U.S. Interagency Council on the Homeless, the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness (referred to subsequently as the Chronic Homeless Initiative, or CHI), involves the participation and funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

The Skid Row Collaborative, the Los Angeles CHI grantee, was a partnership of eleven public and private organizations serving people who are homeless in downtown Los Angeles. Led by the Skid Row Housing Trust and Lamp Community, the Skid Row Collaborative exceeded its goal of housing 62 individuals who were chronically homeless on Skid Row. The Collaborative provided mental health and substance abuse services, primary healthcare and veterans’ services to promote self-sufficiency and residential stability through permanent supportive housing.

Evaluations of the Program

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) and the consortium of Skid Row Collaborative partners sought an assessment of the financial impact the Chronic Homeless Initiative housing program on the use of health care services. The initial scope and objectives of the assessment were to:

Compare the use of local county public services and related costs for two (2) years before and two (2) years after clients were placed in permanent supportive housing through the Skid Row Collaborative, with specific attention to the effect on three County systems: Health, Mental Health, and Jail. Encounters and costs associated that were to be identified included: Emergency Transport and EMS services, emergency room use; inpatient medical and psychiatric services; outpatient mental health treatment; substance abuse treatment (including emergency detoxification); arrests by law enforcement; and time spent in jail.

Key deliverables on the project include encounters of services by a metric that provides the ability to develop cost estimates for each encounter, and cost estimates for determining the fiscal impact of the encounters by system.”

– Excerpt from pg. 2 of the study’s Request for Proposals (RFP), released July 2007. Skid Row Collaborative Cost Avoidance Study (Chronic Homeless Initiative) Los Angeles, California