For most working age homeless people, steady employment is the only feasible avenue to economic independence and a better life. In addition to enabling economic self-sufficiency, work constitutes the single most important link most individuals have with society, offering a foundation for reconnection with the larger community. Looking at homeless individuals in terms of their educational and employment backgrounds and capabilities for work, as well as identifying barriers to their reemployment, gives us a vantage point on the often bleak and intractable phenomenon of homelessness that is both hopeful and pragmatic.

In the absence of data that reliably enumerates Los Angeles County’s homeless population, this report analyzes data from four sources to provide a partial profile of Los Angeles County’s homeless workers and their labor market connections:

- The Census Bureau’s 1990 five-percent Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS).

- Case records and Unemployment Insurance wage and claims data obtained by the Economic Roundtable for 1,256 homeless job seekers served by downtown Los Angeles employment programs in 1991 and 1992.

- n Economic Roundtable survey conducted in 1995 of 139 homeless individuals living on the streets of downtown Los Angeles.

- Life stories of homeless individuals.

Homeless Workers and the Labor Market

Defining characteristics that distinguish homeless workers 16 to 64 years of age from the general county population in the same age range with work histories are that they are extremely poor, more mobile, and much less likely to be married. In the year prior to the census survey, 54 percent of homeless workers had incomes below 26 percent of the poverty level (i.e., less than $1,613), compared to 4 percent of all working age individuals in the county with work histories.

Homeless workers were significantly younger than the Los Angeles County population, much more likely to be African-American, and less likely to be latino, white, or Asian. A majority of homeless workers had obtained a high school degree, and a significant number had some college experience or a college degree. One in three homeless persons with a work history had been employed in service or laborer occupations. Just over half of homeless workers had been employed in professional services, retail, and construction industries.

Seventy-six percent of homeless workers were employed in 1989 or 1990, or both years. The remaining 24 percent of homeless workers can be considered “long term unemployed”. Recent workers were more likely to be latino, and less likely to be white, significantly younger, and better educated than the long-term unemployed. Homeless persons who worked in 1989 were employed for the most part in low wage jobs. The average hourly earnings of homeless workers in 1989 was $6.19, which is equivalent to an annual income of under $12,400. While most homeless workers worked close to 40 hours per week in 1989, they worked an average of only 24 weeks. Thus, like many of the “working poor”, homeless persons were more likely to have worked full-time than part-time hours, but in high turnover, low-wage jobs.

Labor Market Disconnection

The pervasive reality of homeless workers is that they are losing, or have lost, connection with regular employment and opportunities to earn a livable income. The ratio of homeless workers moving in a positive direction to workers moving in a negative direction at the time of the census survey was roughly one to three; 22 percent were maintaining or increasing their labor market connection while 78 percent were moving away from the labor market or had no labor market connection at the time of the census survey.

If the total number of homeless individuals of working age are added to these figures, 31 percent of whom have never worked, it can be estimated that at a given point in time, roughly 15 percent of homeless individuals of working age are maintaining or strengthening a work force connection. Similarly, looking at the total population of working age homeless individuals, including those with no work history, it can be estimated that 35 percent are moving away from the labor market, working declining numbers of hours or having lost all work in the past year, and 50 percent are in a state of stagnant unemployment, having never worked at all or experiencing long-term joblessness. These ratios represent what is occurring at a given point in time rather than the total balance of negative and positive outcomes among people who experience homelessness at some time during the year.

Job Availability and Turnover

A frequently held image of the employment process is that individuals find jobs, successfully adjust to work requirements and become stably employed. This image is contradicted by Employment Development Department data showing that 66 percent of the county’s job openings in low skill occupations (jobs requiring less than one year of training) are the result of workers separating from their jobs rather than job growth. The fact that two-thirds of low-skill job openings result from separations means that employment in this sector of the labor market is not a matter of finding and keeping a job, but rather a matter of finding a succession of jobs. Workers who are socially isolated and lack a family or social network to assist them in finding reemployment are at a disadvantage.

The annual number of job openings projected for Los Angeles County through 1999 by the Employment Development in low-skill occupations, both from separations and industry growth, is 72,948; 48,374 from separations and 24,614 new jobs from industry growth. The number of new jobs is sparse compared to the large number of unemployed and discouraged workers already in the county workforce and the large number of welfare recipients who will be seeking jobs as a result of welfare reform.

Homeless Job Seekers in Downtown Los Angeles

An analysis of agency records for 1,256 homeless job seekers in downtown Los Angeles who participated in employment programs found that most individuals had previously demonstrated their ability to be contributing members of the economy. Three-quarters (77 percent) had held jobs that lasted longer than one year, over half (54 percent) had held jobs that lasted longer than two years, and nearly one-third (30 percent) had held jobs lasting longer than five years.

Information about long-term employment outcomes of homeless job seekers was obtained by linking Social Security numbers of clients served by downtown agencies with records from the State Unemployment Insurance data base maintained by the Employment Development Department to obtain information on employment and earnings of these clients one to two years after they had participated in an employment program.

Information about long-term employment outcomes for homeless job seekers is sobering. Once homeless, lasting employment is persistently elusive. Fifty-nine percent earned nothing and 70% earned less than $1,000 in annual income following their participation in an employment program and search for a new job. Less than 9 percent had annual earnings of $10,000 or more, which would reflect full-time employment at minimum wage.

Surveys of People Living on the Streets

Homeless individuals identified the five factors that are most important when choosing between staying on the street and trying to enter a residential program: (1) protecting their sense of dignity, (2) personal safety, (3) being with friends, (4) having the freedom to do what they want, and (5) finding ways to make money.

The five problems homeless individuals identify as being most important when asked why people go through programs for helping them get off the streets, but still return to Skid Row are, in rank order: (1) there is no money or place to go after people complete programs, (2) people are dropped if they relapse, (3) it is hard to get into residential drug rehabilitation programs, (4) programs don’t last long enough, (5) and programs don’t offer all the needed services.

Respondents indicated that programs need to last much longer than the typical sixty to ninety days to really help people get off the streets. Fourteen to fifteen months was the average program duration identified as being needed to provide adequate support for building a new life. In addition, nearly four out of five respondents said programs should be located outside the downtown area.

Life Stories of Homeless Individuals

A “job club” was organized to gain a clearer understanding of life experiences, individual perceptions, and actual successes and failures of homeless job seekers, as well as provide long-term help to participants. Some of the common themes that emerge from their life stories include:

- By the time they were young adults six out of seven individuals had made significant progress toward holding down jobs and becoming economically self sufficient, the driving force being the energy and optimism of youth. But liabilities carried forward from childhood overtook and derailed this progress.

- All experienced addiction to crack cocaine.

- All have been socially isolated for most of their lives and have not had the support of normal social networks in attempting to solve problems of addiction and employment.

- Nearly all have employment histories, and over half have skills that qualify them for more than one occupation.

- There are infrequent windows of opportunity when individuals were ready to make a serious commitment to recover from addiction and find a job. These intervals of high motivation followed bottoming-out experiences such as incarceration. There were very few support systems to help individuals hold onto the clear thinking they did inside jail when they re-entered the daunting and lonely world outside jail gates. Similarly, it was difficult for individuals to gain admission to a residential drug rehabilitation programs within the window of motivational opportunity if the bottoming-out occurred while they were on the streets.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Many people who are homeless want to have jobs and have the ability to work productively. A smaller number not only want work but have summoned sufficient hope and commitment to make a serious effort at rebuilding their lives and gaining stable housing, employment and personal relationships. The operational implications of this two-tier perspective are that basic opportunities to work and earn survival resources should be available to all homeless individuals, and in-depth support for recovery and for long-term employment should be available if and when individuals are ready for a fundamental commitment to making a new start in their life.

Tier I is local day-labor markets. More than four out of five men and women living on downtown streets said they would accept jobs at minimum wages cleaning up streets. The social costs of failing to provide opportunities for gainful employment, and thereby the dignity of demonstrating one’s worth, are high. Research conducted by California’s Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs found that the average drug and alcohol abuser costs society over $32,000 a year. Basic decency as well as an intelligent understanding of our collective self interests leads us to provide jobs for people who are willing to work. We recommend that local day-labor markets be organized under public auspices to provide jobs for anyone willing to show up at an early hour and meet prevailing employment standards for sobriety and conscientious work efforts. If no private employers need their services, individuals should be entitled to public employment cleaning streets, parks, public buildings, or other useful community services.

Based on the value of minimum-wage earnings, individuals should have the opportunity to work for four or five hours per day, which would entitle them to vouchers for a night’s lodging in a single room occupancy hotel or shelter that provides reasonable privacy and security for possessions, three meals, and a small amount of cash (perhaps $2.50 per day). Individuals who show up for jobs five days a week and work acceptably should be entitled to lodging in a room offering privacy and security for their belongings, and three meals a day, for a week. By paying primarily in vouchers rather than cash the demand for these jobs will largely be limited to the homeless and taxpayers will be reassured they are not paying for drugs or alcohol. Individuals who show themselves to be exceptionally good workers should be rewarded by opportunities for better jobs, more hours of work, training, or improved pay. This will enable some individuals, particularly those who are first-time homeless and cyclical homeless, to find a near-term exit from homelessness. Similarly, individuals with significant rehabilitation needs who demonstrate strong motivation should become candidates for Tier II assistance.

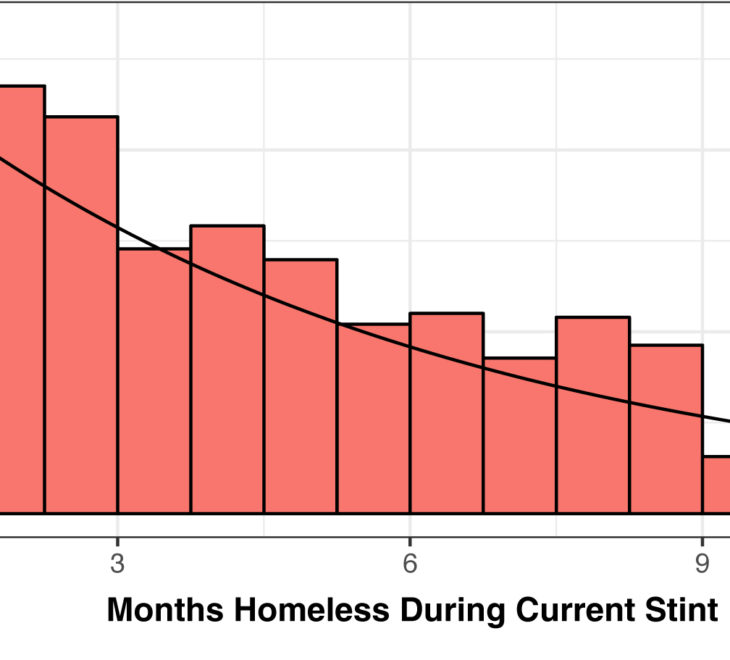

Tier II is comprehensive rehabilitation and employment services for strongly motivated individuals. Most beds in homeless shelters and sleeping spots on streets are occupied by people whose passage into homelessness and subsequent rootlessness and placelessness has lasted longer than a year. Their journey into homelessness has taken time, and similarly the journey out and the process of extricating themselves from the damage done by homelessness takes time. In order to effectively help chronically homeless individuals, programs must offer adequate resources and duration of service to rebuild lasting, stable ties to the larger community. In addition, programs must become adept at recognizing, and acting within, that narrow window of motivational opportunity when individuals are strongly and purposefully determined to rebuild their lives. The central challenge in overcoming homelessness is reconnection of the individual with the larger community. This ultimately manifests itself through success in creating viable, lasting connections around work, housing and social relationships. Essential program ingredients for helping chronically homeless people become stabilized and productively employed include:

- Comprehensive, timely support when there is a window of strong commitment to making a serious effort at building a new life.

- Integrated services offering shelter, food, legal help, drug treatment, income maintenance, health services, personal counseling, development of affirming personal relationships, skill development (where necessary), and job placement.

- Effective employment, training and job placement services that:

- competently assess and respond to client needs and abilities

- develop individualized transition-to-work plans for each client

- channel clients’ skills, interests and aptitudes into demand-occupations

- provide training and supportive services tailored to individual client needs

combine classroom and on-the-job training - ensure that clients have the skills and competencies employers require

place workers with employers who offer stable employment - provide ongoing post-placement support and counseling

- Innovative job creation strategies including public service, entrepreneurial programs and worker-owned cooperatives that make stable employment possible despite severe job shortages in the region and high turnover rates in low-skill jobs.

- Sustained help in the form of nine to twelve months of residential enrollment as well as case management strategies that set high standards for individuals yet maintain connections with them even if they relapse.

- Service delivery environments that replicate the strengths of healthy families, foster honest communication, respect the dignity of each individual and provide spiritual resources for building a new life.

Chapter Headings:

- Executive Summary

- Homeless Persons and the Labor Market

- Profile of Homeless Workers in the 1990 Census

- Labor Market Disconnection

- Job Availability and Turnover

- Homeless Job Seekers in Downtown Los Angeles

- Long-Term Employment Outcomes

- Findings from Surveys

- Life Stories of Homeless Job Seekers

- Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A – Filtering 1990 PUMS Data to Identify Homeless Cases

- Appendix B – Advice from Homeless Persons.