Amazon is flourishing as a corporation. On good days in the stock market it is worth $1 trillion, making it most valuable company on the planet. Amazon has come of age financially. This report examines its standing as a socially accountable corporate citizen, with close attention to the impact of Amazon’s logistics operations on the public balance sheet in the four-county Los Angeles region. This region purchased an estimated $7.2 billion in goods from Amazon in 2018.

Amazon’s trucks hauled an estimated 15.5 billion ton-miles of truck cargo in the region last year, altering how land is used, making heavy use of the transportation infrastructure, affecting air quality, and shaping the economic and living conditions of workers and their families.

Amazon’s trucks hauled an estimated 15.5 billion ton-miles of truck cargo in the region last year, altering how land is used, making heavy use of the transportation infrastructure, affecting air quality, and shaping the economic and living conditions of workers and their families.

Amazon’s warehouses have been welcomed by some communities as a source of jobs and economic growth, but there has not been an assessment of the costs of its presence. As with individuals, communities that have come of age are able to make decisions that shape their own future and safeguard their own well-being. The most successful cities take purposeful action to influence the economy in ways that help workers earn sustaining livelihoods.

Amazon’s customers are concentrated in affluent coastal and hillside neighborhoods, but warehouses and workers are concentrated 60 to 70 miles away in struggling working class communities. This geographic divide reflects the economic polarization and structure of privilege in the four-county region. And public infrastructure and local communities bear the financial and environmental costs of trucking goods from ports to warehouses to consumers. Truck routes from ports to warehouses traverse low-income communities of color, adversely affecting air quality and health in those communities.

The popularity of Amazon attests to its excellent customer care. This report provides a balance sheet from the public perspective to support greater transparency in fiscal policy, broader risk assessment, and financial equity with the employees and communities that drive its profitability.

Impacts on the Land and Air

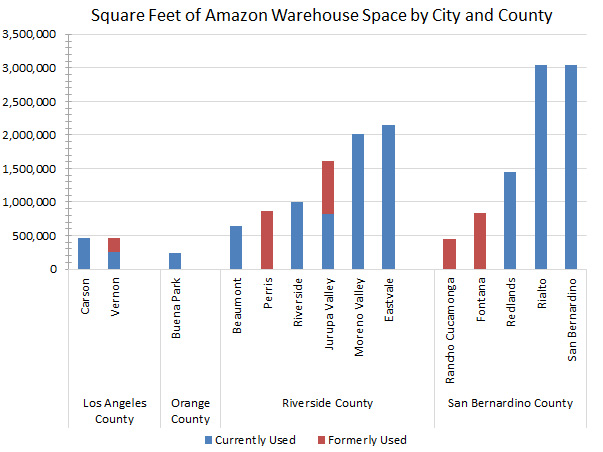

Every day, ships, trucks, trains, and airplanes bring an estimated 21,500 diesel truck loads of merchandise to and from 21 Amazon warehouses in the four-county region. In total, Amazon’s trucking operations in the four-county region in 2018 created an estimated $642 million in uncompensated public costs for noise, road wear, accidents, and harmful emissions.

With an average of 2,180 miles traveled per flight, Amazon’s flights into and out of airports in Riverside and San Bernardino counties released an estimated 620,000 metric tons of CO2 into the atmosphere in 2018. The climate change resulting from those emissions creates an estimated $45 million in social costs for impacts on agricultural productivity, human health, flooding, and ecosystem services.

Impacts on Workers

Amazon’s intense, demanding corporate culture has benefited those at the top, but not necessarily workers who do the heavy lifting of the logistical network that brings packages to our homes. Proximity to lower-income neighborhoods in the four-county region facilitates Amazon’s access to a job-hungry labor force. At the same time, the wages paid by Amazon perpetuate the economic struggle in these neighborhoods.

Amazon’s warehouse jobs are grueling and high-stress. Customer orders must be assembled and delivered on rapid schedules. Warehouse workers wear tracking devices that management uses to monitor where they are at any time, how many steps they take to get their packages assembled, and how long it takes to pick up each item. Those who can’t meet the assembly quotas are terminated.

Most logistics employees are working full-time to support their families but 86 percent earn less than the basic living wage for Riverside and San Bernardino counties. The typical worker had total annual earnings in 2017 of $20,585, which is slightly over half of the living wage. Fourteen percent were under the federal poverty threshold and another 31 percent were just above the poverty threshold.

Most logistics employees are working full-time to support their families but 86 percent earn less than the basic living wage for Riverside and San Bernardino counties. The typical worker had total annual earnings in 2017 of $20,585, which is slightly over half of the living wage. Fourteen percent were under the federal poverty threshold and another 31 percent were just above the poverty threshold.

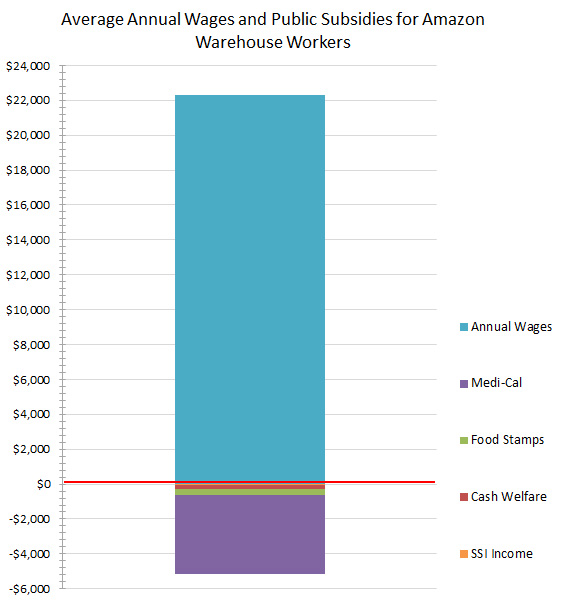

For every $1 in wages paid by Amazon, warehouse workers receive an estimated $0.24 in public assistance benefits. The average annual amount of public benefits per worker is $5,245. The biggest component of public benefits is subsidized health insurance.

Public benefit amounts remain high even for full-time warehouse workers. Workers who were at the job 2,080 hours a year (40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year) received an average of $5,094 in benefits to make up the deficit in the basic needs of their families that were not met by their wages.

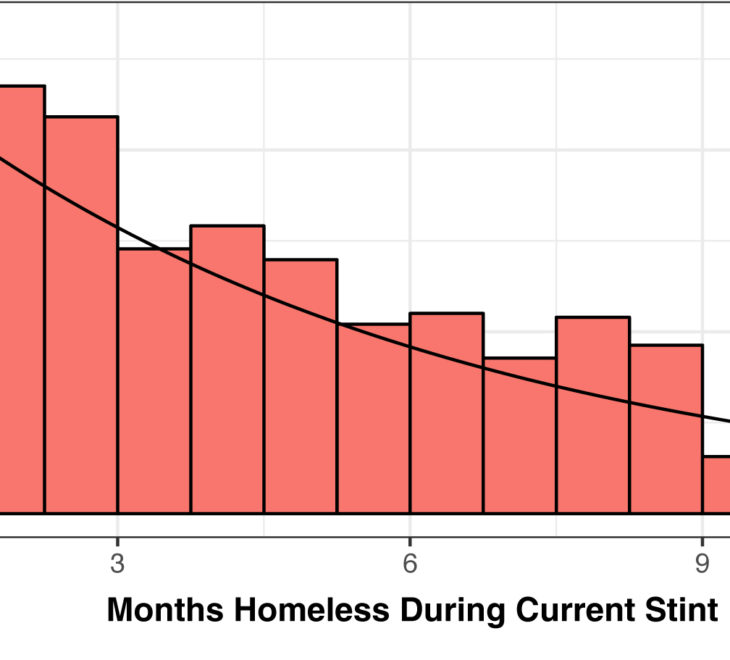

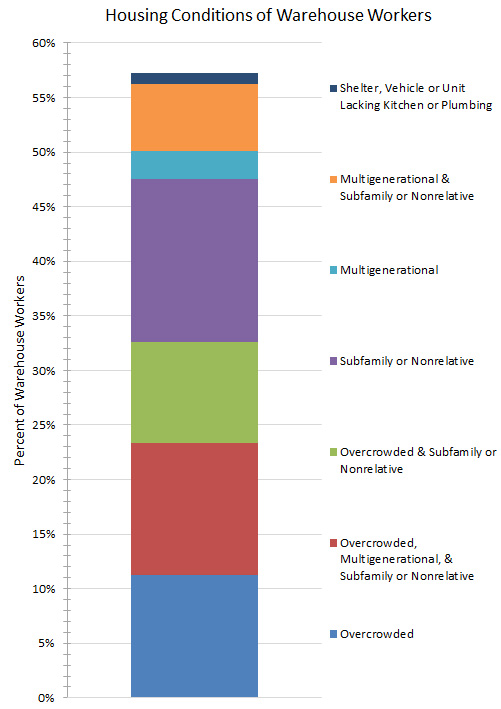

As a consequence of having low wages and insufficient incomes to afford adequate homes for their families, 57 percent of Amazon warehouse workers live in housing that is overcrowded and substandard. There is direct and indirect evidence of significant homelessness among warehouse workers.

As a consequence of having low wages and insufficient incomes to afford adequate homes for their families, 57 percent of Amazon warehouse workers live in housing that is overcrowded and substandard. There is direct and indirect evidence of significant homelessness among warehouse workers.

The economic condition of logistics worker contrasts starkly with workers employed in Silicon Beach and Hollywood in entertainment, computer and mathematics jobs. These workers make a living wage and earn enough to afford housing and buy Amazon products. The higher standard of living they enjoy demonstrates that when the job market or the regulatory environment requires it, Amazon can afford to pay sustainable wages.

Public Oversight

Public Records Act requests were submitted to 39 public jurisdictions where Amazon facilities are located. Nineteen jurisdictions said they had no records related to Amazon. This includes the cities of Jurupa Valley, Riverside and San Bernardino where Amazon has large warehouse facilities and Culver City where Amazon has a major movie production studio.

Seven cities completed environmental impact reports (EIRs), which represent the highest level of local policy analysis regarding Amazon’s impacts. These EIRs supported development of over 36 million square feet of warehouse space and up to 89 plane flights a day. No impacts on the environment, transportation infrastructure or human well-being were identified that warranted stopping a project. Often job creation was identified as the reason for proceeding with a project.

The only benefits that cities are receiving from Amazon’s warehouses are from construction jobs and fees, and employment of residents in low-wage warehouse jobs, along with modest, trickle-down multiplier effects as they spend their sparse earnings. Cities do not receive sales tax revenue from the sale of goods in these warehouses.

The “overriding consideration” put forward in EIRs, that Amazon’s warehouses would provide good jobs and strengthen the economy, does not stand up to scrutiny. This report shows that Amazon’s trucks cause extensive uncompensated damage to public roads and Amazon’s warehouse jobs pay so little that workers can’t afford adequate housing and rely on public assistance. The substandard housing conditions of Amazon’s warehouse workers and their inability to afford food or healthcare for their families weaken the economies of cities.

Public Balance Sheet

Public tools for assessing and regulating Amazon’s impacts are inadequate. The available policy review tools are used infrequently, look only at fragments of Amazon’s local impacts, and show a strong pro-development bias.

A new oversight structure is needed to assess the risk and impacts of Amazon’s activities, and to establish regulatory standards that require the public balance sheet from Amazon’s operations to pay its full costs to the public and to employees.

A new oversight structure is needed to assess the risk and impacts of Amazon’s activities, and to establish regulatory standards that require the public balance sheet from Amazon’s operations to pay its full costs to the public and to employees.

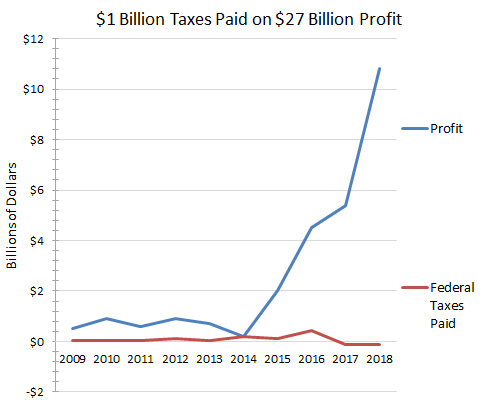

Controversy has surfaced about Amazon’s scant corporate income tax payments and whether it is contributing adequately to the general welfare. Over the past decade, Amazon has paid less than three percent of its $27 billion in profits for federal income tax.

This report uses publicly available data to estimate Amazon’s impacts. The directional findings are sound and often conservative, with methods and sources referenced throughout. Amazon is a data-rich organization with extensive information about wages, working conditions, public subsidies, logistics operations, and carbon footprint. We recommend that Amazon collaborate in improving the accuracy of this public balance sheet.

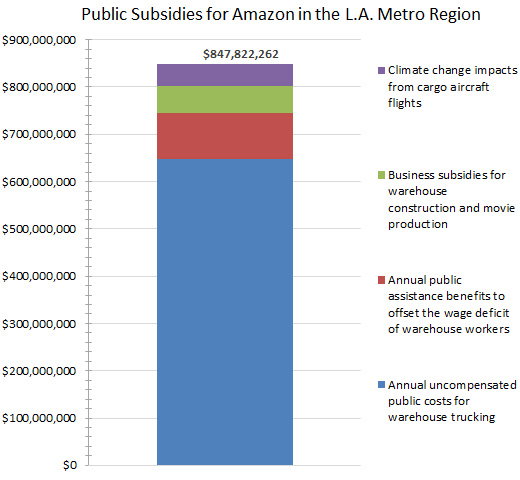

Amazon has received nearly $850 million in public subsidies in the four-county region, some documented in public records, others estimated. This includes:

- $3 million for building construction

- $25 million for movie production

- $30 million for city waivers of traffic impact fees

- $45 million annually for climate change impacts from cargo aircraft flights

- $98 million annually in public assistance for warehouse workers

- $647 million annually in uncompensated public costs for warehouse trucking

This is only a partial list, for example, it doesn’t include public costs to offset the wage deficits of underpaid delivery drivers employed by Amazon and its subcontractors.

This is only a partial list, for example, it doesn’t include public costs to offset the wage deficits of underpaid delivery drivers employed by Amazon and its subcontractors.

Only 7 percent of the public subsidies that Amazon has received are one-time outlays. The other 93 percent of subsidies are ongoing and will recur year-after-year until Amazon raises wages and lowers greenhouse gas emissions.

American society expects that adults will pay their own way in the world, clean up their messes, and reciprocate what others do for them. These expectations are reasonable for corporate citizens as well.

Amazon has grown explosively as an autonomous, fresh thinking, hard driving organization that has taken maximum advantage of every freedom and opportunity allowed it. But it is no longer just an agile adventurer. Amazon is now a dominant force in shaping communities where its logistics operations are located and its workers live. It is restructuring industries, destroying brick-and-mortar retail jobs and replacing them with warehouse and delivery jobs.

Phaeton (cover image) did not know his limits, overreached and fell to his own destruction. Amazon can avoid this fate by finding its footing as an equitable community partner and continue to rise both as an economic success and a corporate citizen.

It is time for Amazon to come of age and pay its own way. This means paying its full costs to the communities that host it and the workers who create its profits. Amazon will benefit when its workers have living incomes because they will have the buying power to purchase the products it sells.

Recommendations

Based on the findings in this report, the Economic Roundtable makes the following nine recommendations for achieving equity in Amazon’s logistics operations:

- Pay a minimum wage of $20 an hour, adjusted annually for cost of living changes, to provide a living income for warehouse workers and delivery drivers.

- Provide comprehensive and affordable health insurance for warehouse workers and delivery drivers and their families, eliminating the need for workers and their families to rely on publicly subsidized Medi-Cal health insurance.

- Allow work breaks for warehouse workers that enable them to remain hydrated, use bathrooms and eat mid-shift meals.

- Provide affordable child care onsite or at nearby child care centers.

- Require logistics subcontractors to provide the same wage floor and benefits as Amazon.

- Invest Amazon’s assets in building affordable housing in communities where its logistics facilities are located as well as the communities where employees from those facilities live.

- Become a partner in local, regional and statewide initiatives to raise the wage floor for the entire logistics sector so that all warehouse, trucking and delivery companies meet the same standards of civic responsibility as Amazon.

- Step up as a leader in reducing climate change impacts by deploying zero emission vehicles and disclosing its full carbon footprint.

- Collaborate in improving and expanding the scope of impact estimates provided in this report to support analysis, planning and policies for reducing the costs and increasing the benefits of the services Amazon provides.

Press Coverage

Staten Island Amazon Unionization Victory and the Crisis of Low Wages in America

By Peace Voice, Black Star News (April 3, 2022)

Amazon ya es tu jefe, tu supermercado, tu televisión y tu Internet. Ahora quiere ser también tu colegio

By Albert Sanchis, Magnet (February 4, 2022)

Una escuela en California tiene “un santuario” para clases antisindicales de Amazon

By El Tiempo Latino (January 27, 2022)

Inland warehouse workers look to a sustainable, equitable future

By Deepa Bharath, Orange County Register (October 18, 2021)

The Quest to Green an Empire of Mega-Warehouses

By Patrick Sisson, Bloomberg CityLab (June 14, 2021)

Amazon seeks to build a distribution center in San Clemente

By Meghann M. Cuniff, Daily Pilot (June 9, 2021)

Amazon triples Southern California warehouse network to deliver packages faster

By Jeff Collins, Orange County Register (March 26, 2021)

Unboxing Amazon – Will the E-Commerce Giant Deliver for Oxnard?

By Kimberly Rivers, Ventura County Reporter (December 2, 2020)

Amazon Delivery Drivers Are Overwhelmed and Overworked by Covid-19 Surge

By Lauren Kaori Gurley, Vice Media Group (July 1, 2020)

Amazon’s Largest Warehouse Hub has a Coronavirus Case. Workers Say Changes Need to be Made

By April Glaser and David Ingram, NBC News (March 26, 2020)

Amazon Announces Massive Hiring Spree As Experts Predict Flagship Prime Delivery Service Will Falter

The Daily Hodl (March 18, 2020)

USA: Amazon ist zum größten Online-Händler der Welt geworden

By Christiane Meier, Weltspiegel – ARD | Das Erste (January 26, 2020)

Activists Build a Grass-Roots Alliance Against Amazon

By David Streitfeld, New York Times (November 26, 2019)

Amazon Prime Will Falter During Coronavirus Crisis, Experts Say

By Lauren Kaori Gurley, Vice Motherboard (March 14 2020)

Over 100 Residents of California’s Inland Empire Occupy Amazon Developer’s Offices

By Lauren Kaori Gurley, Vice Motherboard (January 23, 2020)

Amazon’s impact on workers and the environment

By Madeleine Brand, KCRW Press Play (November 27, 2019)

Here’s what Amazon promised Utah in 2019 and what it has delivered

By Clara Hatcher, The Salt Lake Tribune (January 08, 2020)

Amazon has too much power over our economy: activist

By Nick Rose, Yahoo Finance (November 29, 2019)

Black Friday protesters hit back with ‘Buy Nothing Day’

By Kristin Myers, Yahoo Finance (November 29, 2019)

Black Friday Amazon deals’ costs: Workers’ health, climate change and your own taxes

By Michelle Chen, NBC News, Think (November 29, 2019)

Author of scathing report about Amazon’s impact on its warehouse communities wants Central New York to ‘be aware’

By Andrew Donovan, ABC 9, WSYR-TV, Syracuse, N.Y. (November 27, 2019)

Meet the massive coalition vowing to end Amazon’s ‘powerful grip over our society’

By Arianne Cohen, Fast Company (November 26, 2019)

Amazon pushes back against accusations its warehouses harm the communities that house them

By Evie Fordham, Fox Business News (November 27, 2019)

A new group thinks Amazon is ‘too big to govern’ and wants to lead the resistance

By Juliana Feliciano Reyes, Chicago Tribune (November 27, 2019)

The anti-Amazon movement is gaining steam. Will Black Friday shoppers care?

By Maya Shwayder, Digital Trends (November 27, 2019)

New report suggests Amazon makes some changes before Central New York might want its warehouse

By Andrew Donovan, ABC7 Nexstar Broadcasting (November 26, 2019)

Criticism mounts as ‘peak’ season for Amazon arrives

By Benjamin Romano, Seattle Times (December 1, 2019)

Athena vs. Amazon: New Coalition Debuts on Eve of Holiday Shopping Season to Call Out Company’s “Long Line of Abuses”

By Eoin Higgins, Common Dreams (November 26, 2019)

New Report Outlines Amazon’s Environmental, Labor Damages

By Dees Stribling, Bisnow (November 26, 2019

What Is Amazon Doing To Communities? Report Looks At Tech Giant’s Impact On Los Angeles Area

By Marcy Kreiter, International Business Times (November 26, 2019)

Amazon Abuses Workers and the Climate—Because It Can

By Sonali Kolhatkar, Truth Dig (December 5, 2019)

Amazon’s Bringing More Jobs – And Questions About Its Economic Benefits – To Utah

By John Reed, National Public Radio, KUER Utah (December 4, 2019)

Amazon’s 1-Day Free Shipping Might Do More Harm Than Good. Here’s Why

By Al Root, Barron’s (December 2, 2019)

Criticism increases as the peak season for Amazon arrives

By James Lew, The Media HQ (December 3, 2019)

The Amazon behemoth and its would-be grassroots David

By David Streitfeld, The Philadelphia Tribune (November 28, 2019)

Amazon workers’ injuries spike during holiday season at Illinois facility

By Curtis Black, The Chicago Reporter (December 10, 2019)

Grassroots Opposition to Amazon Coalescing as Groups Protest Working Conditions, Environmental Damage

By Ian Corbin, Karma (November 27, 2019)

Activists take aim at Amazon with new coalition

Business Report (November 26, 2019)

Scathing Reports Document Worker Abuses At Amazon Warehouses Just In Time For Holiday Rush

By Tyler Durden, Zero Hedge (November 27, 2019)

Rapport: Amazon blesse les communautés où il a des entrepôts

Jambon Burst (November 27, 2019)

Dozens of activists groups form national coalition against Amazon

By Kiro Radio Staff, My Northwest (November 26, 2019)

Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) Refutes Claims Of Its Warehouses Harming Communities Housing Them

By Ryan Booth, Argus Journal (November 29, 2019)

Happy? Holidays! Worker injuries spike at Amazon warehouses seasonally, data shows

By Molly Wood, Marketplace Tech (December 3, 2019)

Politico Playbook: Valley Talk

Anna Palmer, Jake Sherman, Eli Okun and Garret Ross, Politico (November 26, 2019)

Scathing reports document negative impacts of Amazon warehouse model

By Linda Baker, Freight Waves (November 26, 2019)

Today’s News & Commentary — November 27, 2019

OnLabor (November 27, 2019)

The effort to challenge the Amazon increasing dominance

By jamesb, Political Dog 101 (November 26, 2019)

(Address geocoding in this report provided by Texas A&M University GeoServices and the US Census Bureau.)