SYNOPSIS

Lack of jobs for California’s labor force has growing costs in the form of poverty, welfare, homelessness, sickness, crime, and diminished futures for the state’s children. The Southern California Inter-University Consortium on Homelessness and Poverty has prepared this report to provide objective information about the broadly shared interest of California residents in reducing the social and personal costs of poverty and welfare.

Homelessness has become one of the dominant social and visual features of urban areas throughout California. The growing number of economically disenfranchised individuals and families living at the most meager level of poverty makes our cities increasingly bleak. This dismal spectacle is neither inevitable nor necessary. The best evidence indicates that poverty and welfare rise and fall with the availability of jobs in the regional economy, and the most effective remedy is a growing economy that offers jobs paying living wages to those wanting to work. Findings from multiple research programs validate the effectiveness of helping people maintain a connection with work and offering them the means to rise out of poverty. Research findings also indicate that the destabilizing effect of eliminating essential safety net programs for people with no resources decreases their success in achieving employment.

The common thread running through this report is the relationship of poverty, welfare and homelessness to the regional economy, and the design of programs that effectively help individuals in poverty build working lives. Californians share a fundamental, pragmatic interest in harnessing tools for shaping the economy and providing human services to increase the share of the state’s residents who are able to be productive and economically self-sufficient. Issues and findings covered in each of the six chapters of this report are as follows.

- California does not have enough jobs for its workforce. California is experiencing the worst and most prolonged period of unemployment since World War II. The current number of jobs in the State is still 2.8 percent less than in 1990. A full count of the unemployed shows 2,230,000 jobless workers, or 14.5 percent of the State’s workforce in 1993. Basic tools for correcting the long-term de-industrialization and wide spread unemployment California is experiencing include encouraging capital investment and job growth in manufacturing industries, and helping those who cannot find jobs remain connected to the work force.

- Welfare caseloads are determined by the economy. Changes in the level of employment in Los Angeles County’s economy account for as much as 81 percent of the changes in its welfare caseload. Availability of jobs for low-skill workers is much more significant than work ethic or skills in determining whether they support themselves through welfare or employment. Welfare caseloads are an index of opportunities offered by the regional economy to support low-skill workers. Successful strategies to create jobs in the regional economy will result in reduced welfare caseloads and are the most realistic approach to reducing welfare.

- Welfare reforms that work must make it possible for people to rise out of poverty. Most welfare recipients are adults with small families who are either working or trying to work. But work is no longer a sure route out of poverty. Many of those who find work return to welfare because of lack of health care, a breakdown in child care, low wages, and temporary jobs. The solution is to enable recipients to remain working by providing support services such as low-cost child care, health insurance, and temporary financial and social assistance at times of crisis. To help the majority of recipients find jobs, training should be replaced by job development and placement programs.

- Loss of safety net programs does not bring increased employment for former recipients. In the two years after Michigan terminated its General Assistance program, only one-third of former recipients found any employment, and most of this was unstable. Most welfare recipients are part of social networks made up of other poor people who are unable to offer even minimal help if welfare ends. Workers “tottering on the edge of subsistence” are less employable than workers whose lives are stable; welfare needs to be available to help jobless people maintain this stability. Families and friends should not be viewed as having the capacity to replace public assistance for low income individuals.

- Welfare recipients are predominantly children. Almost half a million children (22 percent) in Los Angeles County live in families with incomes below the poverty level. Poverty rates have been rising steadily in the County, from 11 percent of the population in 1970 to 17 percent in 1992. Insufficient income increases family stress, impairs parenting skills, and increases risks of developmental difficulties, academic failure, and teenage pregnancy. High levels of poverty among children should be recognized as having future costs, including diminished public resources for providing retirement and health services when today’s workers retire. Childhood poverty is solved through job opportunities for parents, quality child care, and health care.

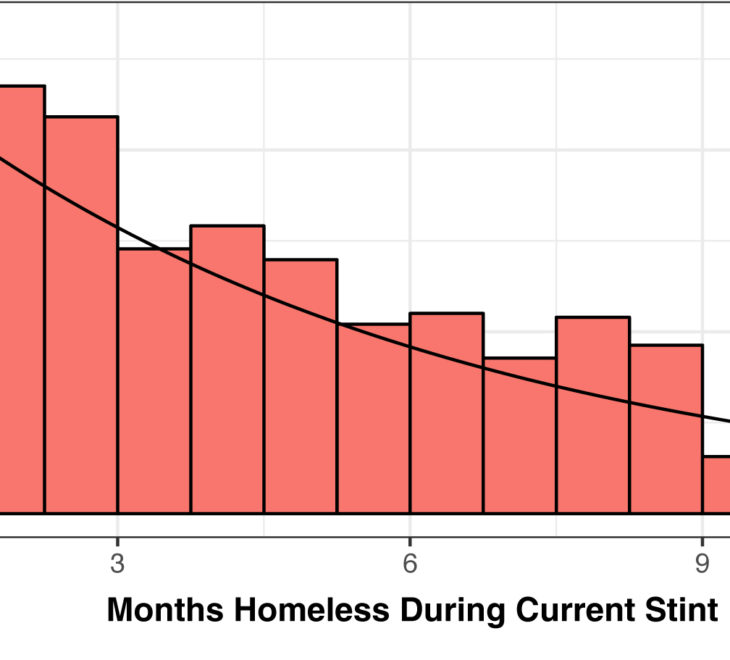

- Homeless job seekers have skills but need stability to be job-ready. Homeless job seekers in downtown Los Angeles are adequately qualified for jobs in terms of education and work history. Yet, only 40 percent find jobs and 9 percent remain employed full-time a year later. Barriers to employment result from lack of reliable, stabilizing social relationships and substance abuse. Over four-fifths of the homeless would accept jobs at $5 an hour cleaning up streets. Long-term employment should be adopted as the most feasible, although difficult, strategy for reducing homelessness. Effective employment programs need to address the full range of problems that undermine stability as well as offer tangible job opportunities to successful graduates. Public funds for cleaning-up Skid Row should be used to provide entry-level jobs for the homeless.

Chapter Headings:

- Introduction

- The Recession that Refuses to Leave

- Welfare Caseloads Determined by Economy, Not Work Ethic

- Challenging Myths About Welfare Recipients

- The Need for Safety Net Programs – the Experience of Michigan

- Proposed Welfare Changes Portend Harm for the Majority of Recipients – Children

- Homeless Job Seekers Have Skills but Need Stability to be Job Ready

- References