Breaking the Fall – Covid Interventions Prevented Homelessness

Struggling workers are either everyone’s responsibility now or everyone’s problem later. When poorly paid workers become jobless at the thin edge of the job market and then unable to pay rent, homeless destitution follows.

In fact, we are equipped with the tools we need to protect workers from the sharper edges of joblessness and to combat homelessness.

Recent government income and housing interventions during the Covid pandemic had demonstrable benefits in reducing the growth of homelessness. Comparisons of projected versus actual growth in Los Angeles County from 2020 to 2022 validate the benefit of these interventions.

In the 2020 Locked Out report, we projected that the Covid recession would cause homelessness to increase 23 percent in Los Angeles, 17 percent in California and 14 percent in the United States from 2020 to 2022. Despite some observable increases in homelessness, increases on this scale did not occur.

This report offers three types of analysis to identify what curtailed homeless growth. First, the homeless count is re-analyzed for accuracy. Estimates for both the 2020 and 2022 counts are adjusted, based on sampling and other observed problems with these counts. Next, encounters between homeless individuals and government institutions are analyzed to understand the trajectory of homelessness during the pandemic. Then, the successful impacts of government interventions are identified.

We conclude by projecting the growth in homelessness if there is a recession in 2023, and recommending steps for curtailing this growth.

Correction of the 2020 and 2022 Homeless Counts

Correction of the 2020 and 2022 Homeless Counts

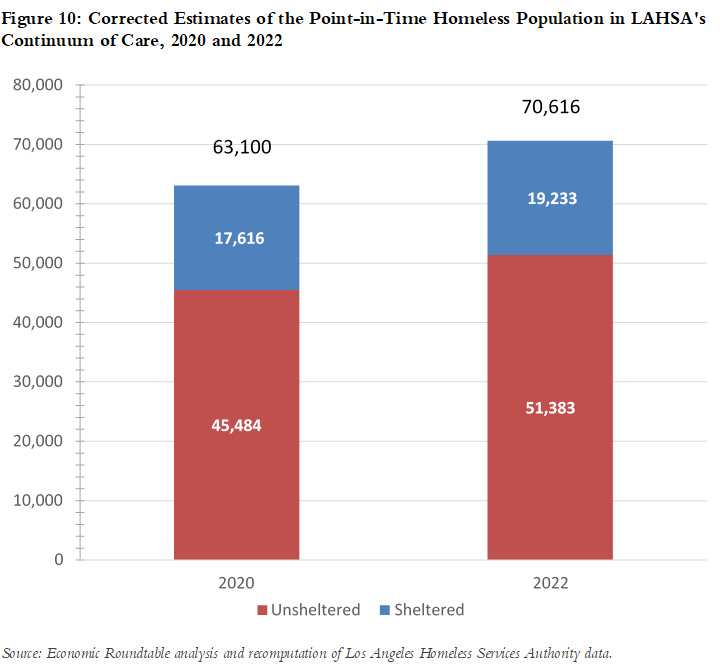

The evidence that the public saw through car windows and that was reported from every metropolitan region in California, except Los Angeles, was that homelessness increased over the two years of the Covid pandemic. However, the 2022 the Los Angeles Continuum of Care (LAHSA) count suggested a different trend, specifically that that unsheltered homeless declined 0.5 percent from 2020 to 2022. Because this appeared implausible, both the 2020 and 2022 counts were re-analyzed.

The corrected 2020 estimate is that the number of unsheltered homeless residents was 1.3 percent smaller than had been estimated by LAHSA, and the unsheltered population in 2022 was 13 percent larger than in 2020.

When the unsheltered population is combined with the sheltered population, which did not require correction, the new estimate of 70,616 total homeless individuals in LAHSA’s continuum of care in 2022 is 11.9 percent larger than the corrected estimate of 63,100 homeless persons in 2020.

Curtailment of Homeless Growth

Overall, it appears that government income and housing interventions during the Covid pandemic reduced the forecasted growth of homelessness by 43 percent in Los Angeles County and 41 percent in California. We estimated that the same reduction in homelessness achieved in California was achieved across the United States.

The growth in homelessness that we projected in 2020 was based on the ratio of growth in unemployment to growth in homelessness found in Los Angeles, California and the United States in the 2008 recession. We applied these ratios to the number of workers who became unemployed in the Covid pandemic to make our projections.

These pessimistic but solidly grounded projections did not materialize. This success in curtailing the growth of homelessness is attributable to government interventions.

Under-Employment and Housing Desperation

Under-Employment and Housing Desperation

To solve the employment upheavals that cause homelessness we have to resist the lure of simple thinking. Instead of looking just at people who are homeless now, we must pay attention to those coming down the tracks – precariously housed workers losing jobs and falling into destitution.

We must learn to value the homelessness that we prevent and do not see, rather than responding just to those who we have failed and see before us on the street.

We need to understand the magnitude of unemployment, the attributes of jobless workers, and become capable of identifying those who are most precariously housed and threatened by homelessness.

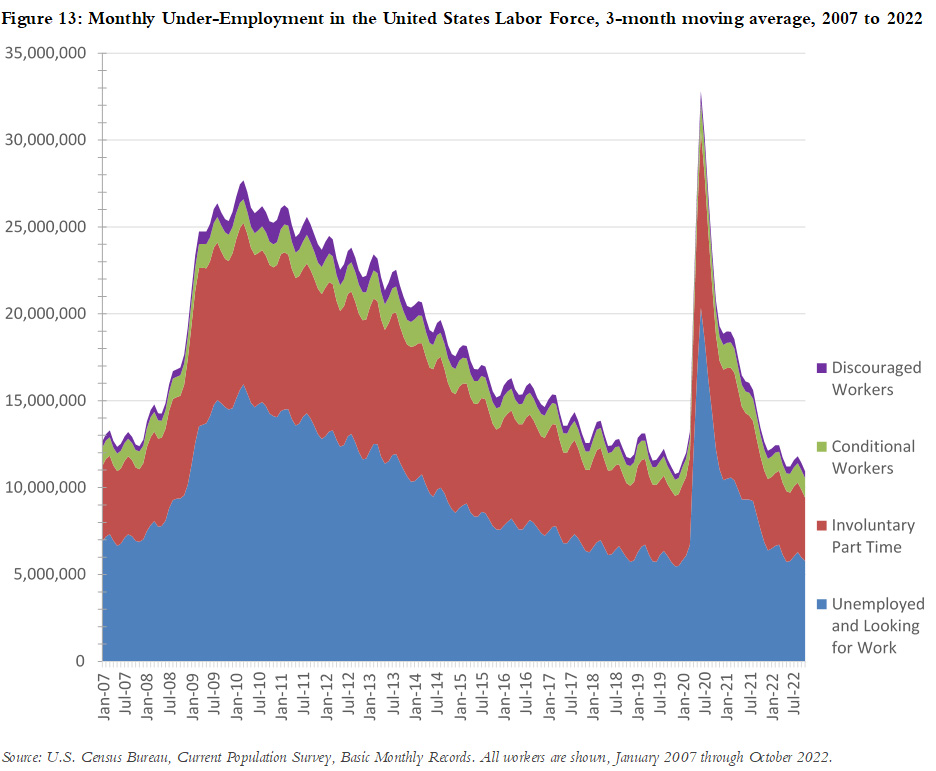

In the first two months of the Covid pandemic, Los Angeles County lost 17 percent of its jobs, California lost 15 percent and the United States lost 13 percent.

This abrupt decimation of jobs was unlike any other recession. In the Great Recession of 2008, it took Los Angeles 21 months to lose 10 percent of its jobs – a smaller job loss in a time window that was five times longer.

Economic homelessness emerges from jobs lost at the thin edge of the labor market, when jobless workers become destitute and are unable to pay rent. The highest rates of precarious housing were among workers with limited education, single parents, Latinos and African Americans. The rates of precarious housing among low-income workers in these groups is twice as high as the total population based on ethnicity, three times as high based on household structure, and four times a high based on education.

Cushioning Unemployed Workers from the Sharper Edges of Joblessness

Cushioning Unemployed Workers from the Sharper Edges of Joblessness

Even when institutions fail to help homeless individuals escape homelessness, the record of those encounters exposes the contours and trajectory of homelessness.

Records during the Covid pandemic are available for hospital care of homeless patients in California and Los Angeles, homeless deaths, arrests, encampment sweeps, and cash aid in Los Angeles. These records shed light on the course of homelessness during the pandemic as well as institutional practices that ameliorated, and in some cases worsened, homelessness.

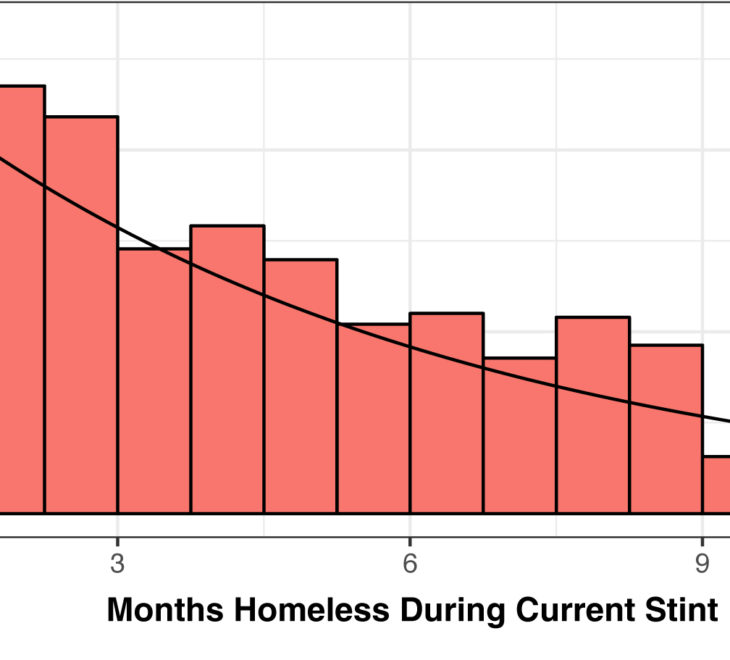

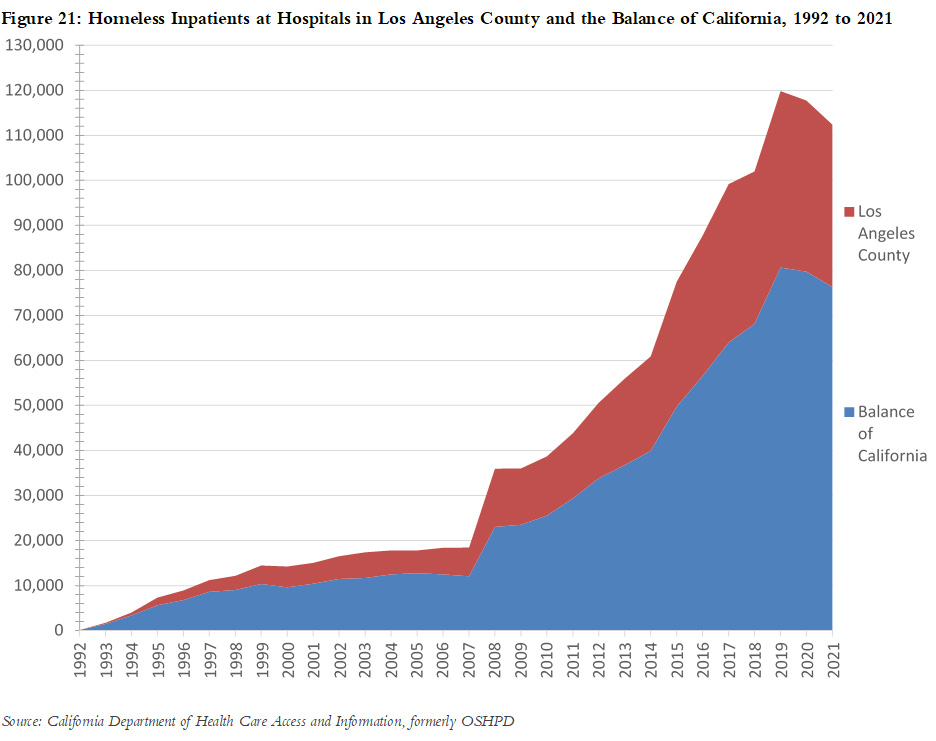

Hospitals have become a primary institutional touch point for homeless individuals. The number of homeless inpatients reported by hospitals is 900 times larger now than it was 30 years ago. The primary medical diagnosis for inpatients is a psychotic mental disorder. Not surprisingly, these conditions emerge and become more acute over the course of extended homelessness. This is a compelling reason for providing earlier, more effective interventions to identify and help individuals who are likely to become persistently homelessness.

There was a 56 percent increase in deaths among homeless individuals during the first year of the pandemic. This includes a 78 percent increase in deaths from drug overdoses. These are deaths of despair and evidence of the damaging effect of social isolation during the pandemic.

The number of calls from Los Angeles residents asking the city to clean up homeless encampments increased by 60 per month after the onset of Covid. The most likely explanation for the increase is that the number of unsheltered dwellings increased. The long-term ineffectiveness of dispossessing and dislocating unsheltered homeless individuals speaks to the need for both more housing and more sustaining sources of income.

The County of Los Angeles terminated 28,435 individuals from the General Relief caseload at the height of unemployment during the Covid pandemic. This action appears to have been driven by an arbitrary administrative decision rather than lack of eligibility and is likely to have caused greater hardship among homeless recipients.

Interventions

Interventions

Housing and income interventions during the Covid recession and the ensuing wave of unemployment reduced the growth of homelessness by almost half and can provide the same protection in future recessions. Scaling-up re-employment interventions for high-risk unemployed workers would further reduce homeless risks.

The moratoriums on eviction provided the greatest protection against homelessness, reducing the number of evictions nationwide by half, and providing even stronger protections in California and Los Angeles.

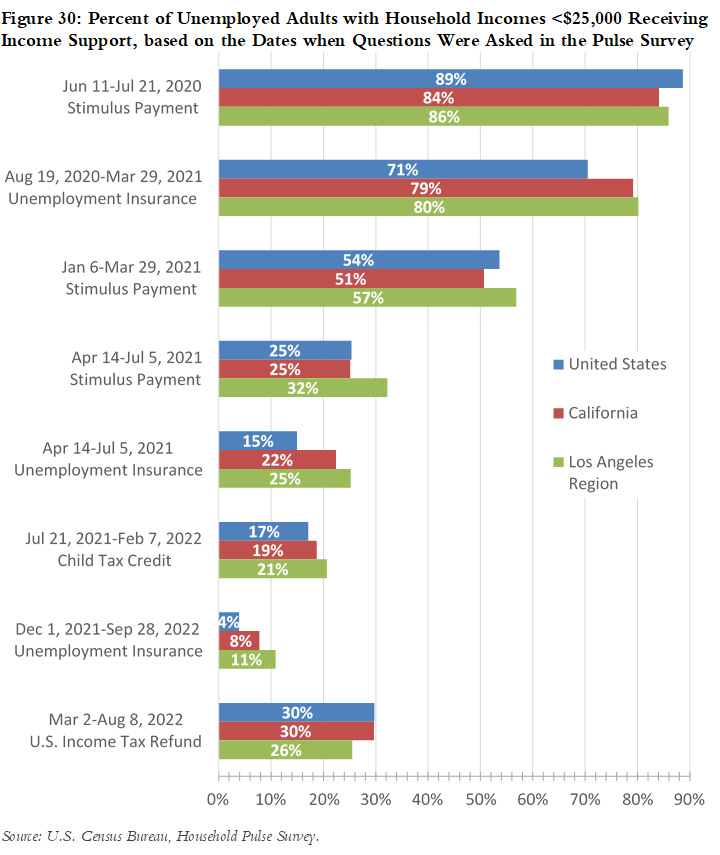

Cash income from unemployment insurance and stimulus payments provided parallel support for most unemployed, low-income workers until mid-2021. These payments forestalled destitution and reduced the risk of homelessness.

Roughly one-fifth of vulnerable workers benefited from the expanded child tax credit, and a small fraction of the labor force benefited from rent relief and the Paycheck Protection Program.

The homeless housing system provided minimal support, with the exception of a large increase in emergency shelter beds in most California counties, except for Los Angeles, which reported almost no increase in the number of occupied shelter beds.

Re-employment interventions were almost nonexistent, even though unemployment caused the economic crisis. Re-employment of homeless workers calls for rebuilding hope and purpose to open a path for achieving their productive potential.

For example, the Realization Project is demonstrating how interventions that both restore the human spirit and connect high-risk unemployed workers with jobs can be effective. The resource library from this project is placing the predictive screening tools, the curriculum and lesson material in the public domain.

Breaking the Fall Next Time

Breaking the Fall Next Time

Eviction moratoriums and cash payments kept households and workers intact during the Covid pandemic. These two interventions worked.

The truly obvious and massive problem that causes homelessness in recessions is lack of employment. To solve homelessness, we need a searching, open and good faith dialogue about restorative economic justice and jobs.

The true answer to homelessness is that we must do a better job correcting our nation’s structural social and economic inequities.

Re-employment is a third, crucial intervention. This strategy has been under-utilized and should be a primary tool for combatting homelessness among low-income, high risk and unemployed workers.

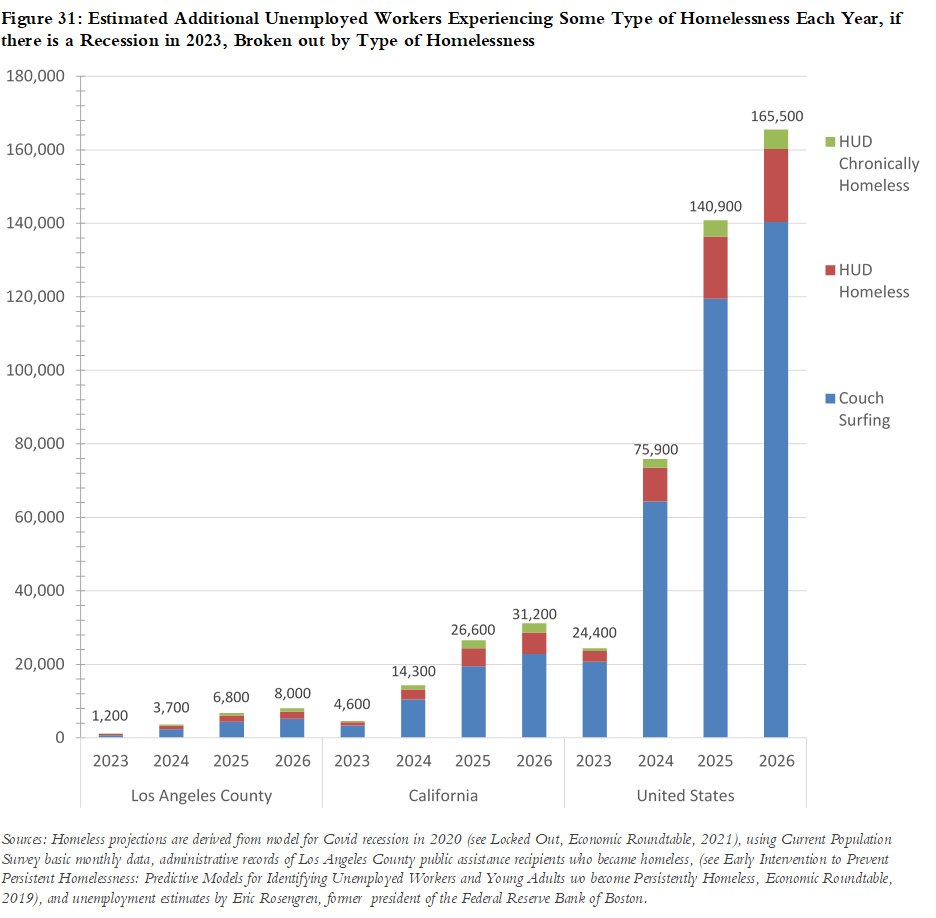

A mild recession in 2023 appears to be a strong possibility, caused by increases in interest rates by the Federal Reserve Bank.

If there is a recession in 2023, we project that unemployment in the United States will increase from 3.7 percent now to 5.25 percent. This level of unemployment would cause an estimated 7,040 individuals who meet HUD’s definition of “sleeping in a place not meant for human habitation” to become homeless in Los Angeles County over the coming four years.

They are projected to be accompanied by a total of 20,560 individuals in California and 61,810 in the United States who also will be sleeping in places not meant for human habitation.

We can apply five important lessons about the 2020 interventions to replicate and improve on our most successful measures for closing the pipeline from unemployment to homelessness.

First, Do Not Rely on the Homeless Services System to Prevent Homelessness

The homeless social services and housing system is largely reactive rather than preventative in addressing homelessness. Furthermore, the system does not have adequate resources to ensure incomes and housing for all unemployed workers at risk of homelessness. It is the responsibility of mainstream public systems to provide income support and protect housing.

Second, Keep People Housed – Prevent Evictions

Eviction moratoriums appear to have been the most effective intervention in preventing housing displacement and homelessness. Tools for keeping vulnerable workers in housing include ordinances that prohibit evictions, legal assistance for households facing eviction, and income supports that enable households to pay rent.

Third, Money – Maintain Incomes

Income is the most essential tool for keeping workers housed. This can be provided in the form of cash aid, rent assistance or earned income.

Fourth, Work – Reconnect Workers with Jobs

The workers who are most vulnerable to homelessness are also likely to have the greatest difficulty becoming re-employed. Paying for housing with earned income meets the essential interests of both workers and the public. Reconnecting workers with jobs may require hands-on assistance in finding employment along with restorative justice support for inner healing to overcome trauma.

Fifth, Target Interventions on High-Need Workers – Use Smart Data

Interventions should selectively target unemployed workers who are most vulnerable to becoming homeless. The society-wide interventions during the Covid pandemic were one-time events in response to a national trauma. Funding will not be available to replicate income and housing interventions on this scale. However, interventions for preventing homelessness were tested and validated during the Covid pandemic and can be more narrowly targeted based on the scale of available federal, state and local funding.

Predictive analytic screening tools such as those used in the Realization Project are in the public domain. They can accurately identify unemployed workers who are likely to become persistently homeless. These tools should be used to target cost-effective interventions that lead to productive re-employment rather than persistent homelessness.

Improve the Accuracy and Reliability of the Homeless Count

We do not know where we are or where we are going without a map. It is the job of the homeless count to provide a map of homelessness, however this effort in Los Angeles County was flawed and unreliable in 2022.

Recommendations for improving the accuracy and reliability of the count for understanding and combating homelessness include:

Establish a more independent and reliable count process

1. Establish a peer-review process for the homeless count before it is released to obtain expert and independent assessments of the reliability of the count and recommendations for improving the analysis of data before the final count is released.

2. Give the research organization working with the homeless count a fully independent voice, including independence in releasing data, research findings and recommendations regarding the count.

3. Assess whether the comprehensive information for individuals receiving homeless services and housing provides a more reliable population profile than the demographic survey and should have a role in describing the street population in addition to the sheltered population.

Improved specific count practices

4. Conduct the demographic survey as a uniformly random component of the street count rather than as an activity that is disconnected in time and space.

5. Increase the number of families with children that are reached by the demographic survey to provide samples of at least 100 for subgroups that are used in producing demographic estimates.

6. Make it a primary goal of the count to calibrate year-to-year comparability in population estimates and to identify likely causes for shifts in the number or composition of the homeless population.

7. Improve the reliability of the count by identifying, quantifying and correcting undercounts. This includes conducting surveys at homeless provider locations in the days following the count using a questionnaire designed to determine whether homeless respondents were included in the count.

Use information from the demographic survey to improve homeless outcomes

8. Encourage independent research using information from the demographic survey that is operationally important for combating homelessness, for example, barriers to employment, health conditions, justice system involvement, and needed services.

Press Coverage

Why Are California Policymakers Taking Steps to Make the Homeless Problem Worse?

By Jonathan Vankin, California Local (August 3, 2023)

LA City Council to expand tenant protections with expected start in February

By Sharla Steinman, Daily Bruin (January 27, 2023)

LA’s Homeless Count Underway, After Being Criticized for Methodology, Possible Undercounts Last Year

By Jamie Joseph, The Epoch Times (January 25, 2023)

LA County supervisors extend eviction moratorium to end of March

By Jason Ruiz, Long Beach Post (January 24, 2023)

With An Audit Looming, LA’s Homeless Count Moves Forward This Week

By Julia Barajas, LAist (January 23, 2023)

Editorial: L.A.’s eviction moratorium will end, but tenant protections should continue

By the Times Editorial Board, Los Angeles Times (January 10, 2023)

As LA’s COVID tenant protections expire, some fear eviction wave

By Eric He, HEY SOCAL (January 5, 2023)

New Study Shows Government Aid Prevented More Homelessness

By Robert Davis, Invisible People (January 3, 2023)

‘Nowhere close’: LA accused of fudging homelessness numbers

By Kevin Haggerty, American Wire News Service (December 24, 2022)

Los Angeles County Follows City, Extends COVID-Era Eviction Moratorium

By Jill McLaughlin, The Epoch Times (December 24, 2022)

Pandemic eviction protections, direct payments kept homelessness in check, study shows

By Doug Smith, Los Angeles Times (December 15, 2022)

Ayuda del gobierno evitó que la indigencia aumentara un 23% en Los Ángeles

By Jacqueline García, La Opinión (December 15, 2022)

250,000 Unemployed U.S. Workers Were Saved From Homelessness By Government Help In The COVID-19 Recession

By Random Lengths News, (December 19, 2022)

Pandemic resolutions for the new year (and beyond)

By Karen Kaplan, Los Angeles Times (December 20, 2022)

New Report Finds LA’s Homelessness Crisis Was Curbed By Government Economic Assistance

By Larry Mantle, Air Talk, KPCC (December 15, 2022)

Eviction Protections, Payments Kept Homelessness In Check In L.A., Study Shows

By California Healthline (December 15, 2022)

Eviction protections, payments kept homelessness in check in L.A., study shows

By Alley Einstein, US Times Post (December 15, 2022)

Executive order from Mayor Bass aims to speed approval of affordable housing

By Steven Sharp, Urbanize (December 19, 2022)